The Chromebook E-Waste Crisis: Three Years After the Alarm, Has Anything Changed?

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

A disclosure before we begin: Starryhope covers Chromebooks extensively and generally recommends them as excellent devices for most people. We have a financial interest in people buying Chromebooks. You should weigh what follows knowing that, and consider it a sign of how seriously we take this issue that we’re writing about it anyway.

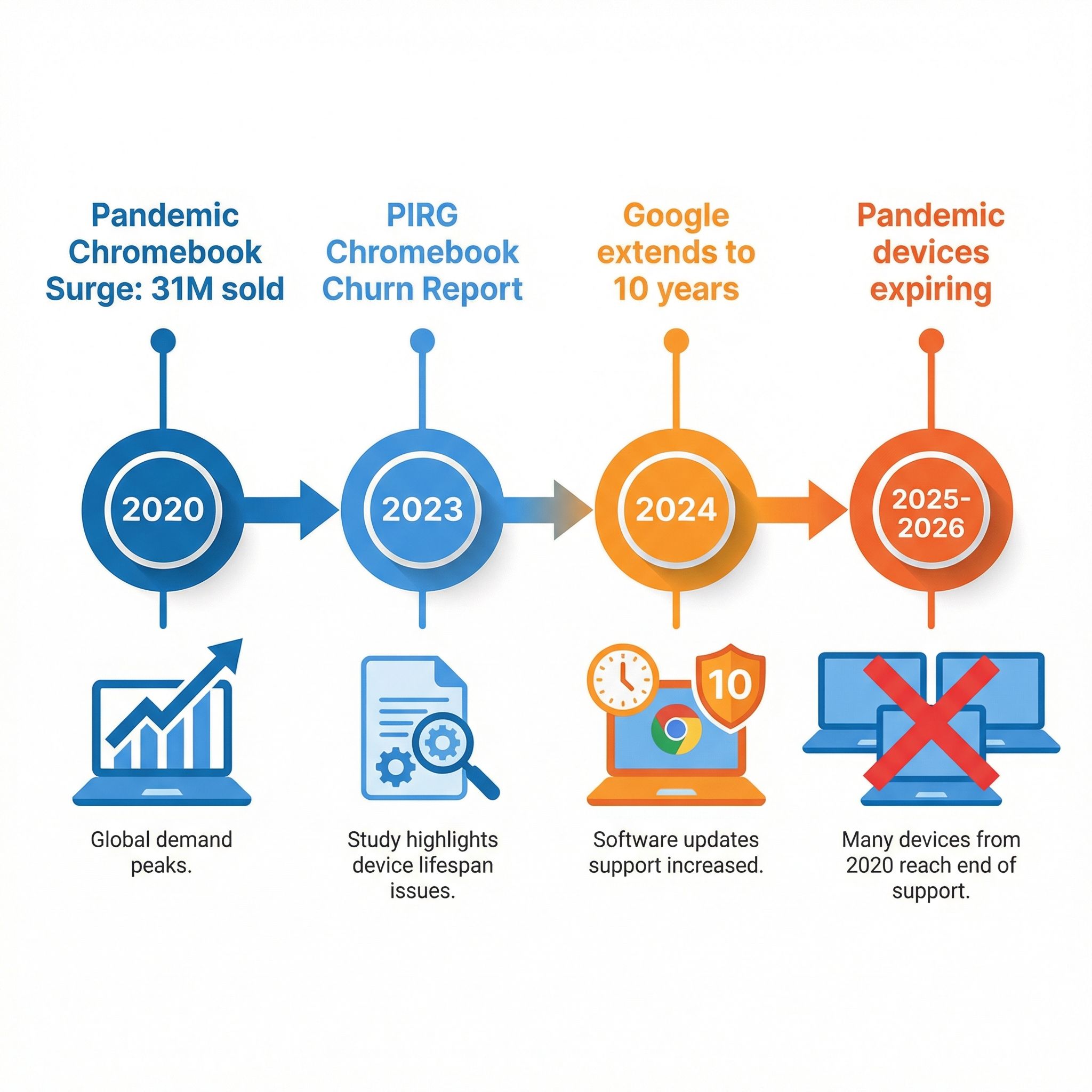

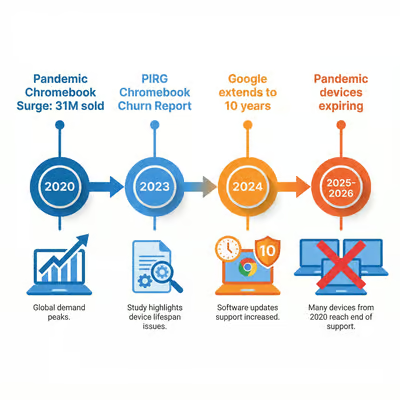

In April 2023, the U.S. Public Interest Research Group published a report called Chromebook Churn that landed like a grenade in the education technology world. The numbers were staggering: school Chromebooks lasted an average of four years, only a third of the resulting e-waste was properly recycled, and the manufacturing emissions from just the Chromebooks sold during 2020 were equivalent to putting 900,000 additional cars on the road. PIRG called for ten years of minimum software support, and the story got picked up by PCWorld, PC Gamer, and dozens of other outlets. It felt like a turning point.

Then Google actually listened. In September 2023, the company announced that all Chromebooks released from 2021 onward would receive ten full years of automatic updates. Problem solved, right? Three years later, the answer turns out to be more complicated than anyone hoped.

The Pandemic Chickens Come Home to Roost

To understand why the e-waste crisis hasn’t gone away, you need to understand the scale of what happened during the pandemic. In the last quarter of 2020 alone, Chromebook sales were 287 percent higher than the year before. Schools that had never considered one-to-one device programs suddenly needed a laptop for every student, and Chromebooks were the obvious choice at $200 to $300 per device. Over 31 million Chromebooks were sold globally in that first pandemic year, and the vast majority went to schools.

Those devices were not manufactured in 2020, or even 2021. Many were models whose hardware platforms had been certified years earlier, meaning their Auto Update Expiration clocks were already ticking when they came out of the box. A school that bought an Acer Chromebook Spin 311 in the fall of 2020, for example, was buying a device whose AUE date was June 2026. That’s not ten years of support. That’s six years from purchase, and the device itself still works perfectly fine.

This is the wave that’s hitting right now. Dozens of Chromebook models purchased during the pandemic are reaching their expiration dates in 2025 and 2026, and Google’s ten-year extension only applies to devices released from 2021 onward. The very machines that schools bought in their moment of greatest need are the ones falling off the support cliff first. While some models received retroactive extensions of two to three years, many others did not, and the resulting patchwork of expiration dates has left school IT departments scrambling to figure out which devices can stay and which have to go.

What “Expiring” Actually Means

If you’re not familiar with the concept, Auto Update Expiration is the date after which a Chromebook stops receiving ChromeOS software updates, including security patches. The device doesn’t stop working. You can still turn it on, open Chrome, browse the web, use Google Docs, and do everything you did yesterday. The hardware is unchanged. But without ongoing security updates, the device becomes increasingly vulnerable to exploits, and Google’s official position is that it should no longer be considered safe for environments where sensitive data is handled.

For a parent using an expired Chromebook to check email at home, this is a manageable risk. For a school district managing thousands of devices that access student records, testing systems, and educational platforms governed by federal privacy regulations like FERPA, it’s a genuine problem. IT administrators aren’t being paranoid when they pull expired devices from service. They’re responding to real compliance requirements and legitimate security concerns that come with running outdated software on machines that handle children’s data.

The frustration isn’t that Google updates its software. Every platform does that. The frustration is that the timeline is tied to when the hardware platform was certified, not when the device was purchased. A family buying a clearance Chromebook in 2024 might unknowingly purchase a device that expires in 2026, and nothing on the box will warn them. We’ve covered how to check your AUE date in detail, and if you’re shopping for a Chromebook, checking that date should be step one.

The Environmental Toll Nobody Wants to Talk About

The environmental case against short device lifespans is straightforward and damning. Manufacturing a laptop consumes enormous resources: rare earth minerals mined in conditions that are frequently exploitative, energy-intensive fabrication processes, and global shipping networks that add carbon at every step. The information technology sector produces roughly as much greenhouse gas emissions as the airline industry, and every laptop that gets replaced before its hardware fails represents wasted embodied energy that no amount of recycling can fully recover.

And recycling itself is barely happening. When Chromebooks reach their expiration dates, only one-third of the resulting electronic waste is properly recycled. The rest ends up in landfills where lead, mercury, cadmium, and other hazardous materials can leach into soil and groundwater. Electronic waste represents less than two percent of the global waste stream by volume but causes over 70 percent of its toxic environmental effects, according to United Nations data. These aren’t abstract statistics. They describe real chemicals entering real ecosystems because functional hardware is being discarded on a software company’s schedule.

PIRG calculated that doubling the lifespan of just the Chromebooks sold in 2020 would save 8.9 million tons of CO2 equivalent emissions and cut costs equivalent to taking 900,000 cars off the road for a year. Across the 48.1 million K-12 public school students in the United States, extending device lifespans could save taxpayers $1.8 billion. Those savings would go directly back to schools that are perpetually underfunded and forced to make impossible choices between technology budgets and everything else students need.

What Google Got Right (And What It Didn’t)

Let me give credit where it’s due. Google’s decision to extend Chromebook support to ten years was a meaningful response to a real problem, and it happened faster than most people expected. When a company that derives revenue from hardware replacement cycles voluntarily extends the life of its products, that’s worth acknowledging. The ten-year policy puts ChromeOS ahead of most of the industry: many Android phone manufacturers still offer only two to three years of updates, and Microsoft’s decision to drop Windows 11 support for pre-eighth-generation Intel processors drew similar criticism.

The problem is that the extension was not retroactive in a meaningful way. Devices released before 2021 received modest extensions of two to three years, but many popular school models still face imminent expiration. And even ten years may not be enough when you consider how school budgets actually work. A district that buys Chromebooks in 2026 will receive updates until 2036, which sounds generous in the abstract. But school technology funding often relies on bond measures, grants, and one-time federal allocations that create boom-and-bust procurement cycles. The pandemic funding that enabled the great Chromebook purchasing spree is long gone. When those ten-year-old devices expire, there may not be a budget line item waiting to replace them.

Google has also taken steps to make Chromebooks more repairable. The company’s Chromebook repair program partners with manufacturers like Acer and Lenovo to identify repairable models and provide repair guides, tools, and replacement parts. Some districts have even launched student repair programs where kids earn course credit while fixing school devices, saving districts real money. San Ramon Valley Unified in California harvests parts from broken devices in partnership with parent clubs. One district reported saving $90,000 by recycling components from unfixable machines.

But repairability doesn’t solve the fundamental problem. You can replace a cracked screen or a dead battery, but you can’t replace an expired software update. A Chromebook with a brand new keyboard and a freshly installed SSD becomes e-waste on the same day as one held together with tape, because the software expiration doesn’t care about the condition of the hardware.

The $327 Million Question

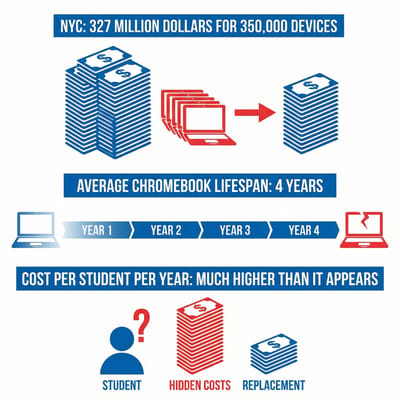

If you want to see what the Chromebook replacement cycle looks like in practice, look at New York City. In September 2025, Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to distribute 350,000 new internet-connected Chromebooks to public school students at a cost of roughly $327 million, including the devices themselves and four years of cellular connectivity through T-Mobile. Priority went to schools using devices more than five years old, which is another way of saying schools whose pandemic-era Chromebooks had aged out of usefulness.

The NYC program is well-intentioned, and there’s a genuine digital divide that affects students in the city: more than 22 percent of Bronx households lack home internet. But as New York Focus reported, it’s not clear that 350,000 students actually needed new devices. The city’s K-12 enrollment is about 793,000, and a 2020 state report found that only 13 percent of NYC public school students had insufficient internet access, a figure that has likely shrunk since then as free internet programs expanded. The spending was possible partly because the city had negotiated a deal with T-Mobile for city operations, effectively subsidizing the program. It’s a reminder that Chromebook replacement cycles aren’t just an environmental story. They’re also a story about how public money gets spent, who benefits from the spending, and whether the people writing the checks are asking hard enough questions about whether the old devices actually need replacing.

This isn’t a problem unique to New York. School districts across the country are facing the same calculus: their pandemic Chromebooks are aging out, replacement funding is uncertain, and the pressure to stay current creates a rolling wave of procurement and disposal that benefits device manufacturers while straining school budgets. The devices themselves are affordable. The replacement cycle is not.

Solutions That Actually Exist (And Their Limitations)

For individual Chromebook owners facing an expired device, the options are better than they were three years ago, even if none of them are perfect. ChromeOS Flex is a version of ChromeOS designed for older hardware, and while Google doesn’t officially support installing it on expired Chromebooks, plenty of users have done so successfully. The process isn’t straightforward on Chromebooks specifically, as it requires disabling firmware write protection and potentially flashing custom firmware, but it works. The catch is that it’s an unofficial solution that Google could break at any time, and it requires a level of technical comfort that rules it out for most schools and families.

Installing Linux on an expired Chromebook is another option, and it’s one that Starryhope’s audience is well-positioned to explore. Modern lightweight Linux distributions like Linux Mint XFCE or MX Linux can turn an expired Chromebook into a perfectly functional computer for web browsing, document editing, and light productivity work. The hardware hasn’t gotten slower just because Google stopped updating the software. For a tech-savvy parent or a school with an IT department willing to experiment, Linux can extend a device’s useful life by years.

The more systemic solutions require changes from Google and from the broader industry. PIRG has continued pushing for legislation that would require minimum support periods for consumer electronics, and the right-to-repair movement has gained significant momentum. Oregon, California, Minnesota, and Colorado have all passed right-to-repair laws that make it easier for consumers and independent shops to fix devices. These laws haven’t specifically addressed software expiration, but they’re part of a broader shift toward holding manufacturers accountable for the full lifecycle of their products.

The Framework Laptop Chromebook Edition deserves a mention as proof that a repairable, upgradeable Chromebook can exist. Framework’s modular design lets users replace everything from the screen to the keyboard to the memory, and the device ships with a screwdriver because they actually expect you to open it. But at $999, it costs three to five times what schools pay for standard Chromebooks, and even Framework can’t solve the software problem: the Chromebook Edition’s AUE date is June 2030. Repairability is necessary but not sufficient. The real fix has to come from the software side.

What Needs to Change

The Chromebook e-waste problem is not unsolvable. It’s not even particularly complicated. The hardware lasts longer than the software support, and the entity that controls the software support is making a choice about when to end it. That choice has environmental and financial consequences that are borne by schools, taxpayers, and the planet rather than by the company making the choice.

Google should make ChromeOS Flex officially supported on expired Chromebook hardware. The company already maintains ChromeOS Flex for old Windows and Mac laptops. Extending that support to its own expired devices would be a straightforward acknowledgment that functional hardware shouldn’t become e-waste because of a software decision. It would cost Google very little, since ChromeOS Flex already exists, and it would eliminate the single biggest driver of Chromebook e-waste.

Beyond that, the industry needs to decouple software support timelines from hardware refresh cycles. Apple has shown this is possible: the company routinely supports Mac hardware for seven or more years of macOS releases, and even dropped models continue receiving security patches for older versions. Google’s ten-year policy is a step in that direction, but it should be a floor, not a ceiling. If the hardware works, the software should support it. The argument that older hardware “cannot support” new updates often reflects a choice about development priorities rather than a genuine technical limitation.

For schools, the answer is better procurement planning that factors in total cost of ownership rather than sticker price. A $300 Chromebook that lasts four years costs more per year than a $500 device that lasts eight. Districts should prioritize models with the longest possible AUE dates, budget for repairs rather than replacements, and demand that manufacturers provide spare parts at reasonable prices. The Chromebook comparison chart on this site includes AUE dates for every model precisely because we think this information matters as much as processor speed or screen size.

The PIRG report was the alarm bell. Google’s response was meaningful but incomplete. Now it’s 2026, and the pandemic Chromebooks are actually expiring. The question isn’t whether this is a problem. The question is whether we’re going to keep buying our way out of it every four to five years, or whether we’re going to demand that the devices we buy for our kids are designed to last as long as the kids need them.