The Chromebook Screen Time Debate: What the Research Says and What Parents Can Do

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

Listen to this article:

A disclosure before we begin: Starryhope covers Chromebooks extensively, links to Chromebook products, and generally thinks they’re solid devices. You should weigh what follows knowing that we have a natural interest in Chromebooks being seen favorably. That said, honest analysis matters more to us than cheerleading, and the screen time research raises concerns that deserve a straight answer rather than defensive deflection.

In November 2025, psychologist Jean Twenge published an op-ed in The New York Times titled “The Screen That Ate Your Child’s Education,” and the resulting conversation has fundamentally shifted how parents and educators think about school-issued devices. Her core argument is blunt: the “every kid gets a Chromebook” idea has been a failure. Test scores are down. Screens are bad for learning. Kids use school-issued devices to watch streaming services, YouTube, and worse. The piece struck a nerve because it articulated something many teachers and parents had been feeling but couldn’t quite name. Within weeks, it had become the most shared education article of the year.

But declarations of failure deserve scrutiny, especially when they concern technology that 50 million students and educators use every day worldwide. The reality, as you might expect, is considerably more complicated than a single op-ed can capture.

What the Research Actually Shows

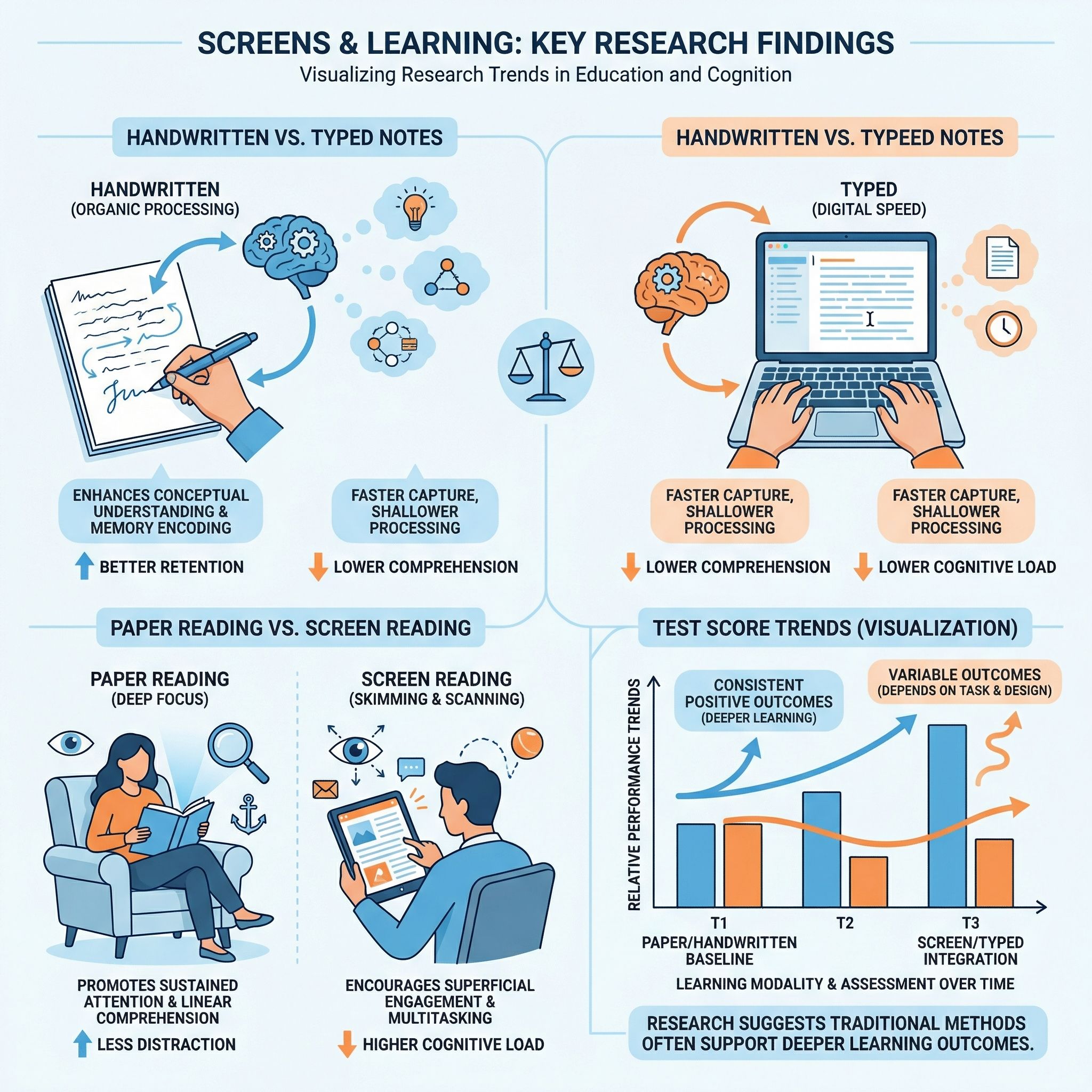

Let me be clear about something uncomfortable: there is legitimate research suggesting that screens can hurt learning. Dismissing that research because it’s inconvenient for anyone who writes about Chromebooks would be dishonest. A 2024 meta-analysis led by Abraham Flanigan analyzed 24 studies and found that college students who took handwritten notes were significantly more likely to earn higher course grades than those who typed on laptops. The researchers argue that handwriting’s slower pace forces students to process and synthesize what they hear rather than transcribing lectures verbatim. It is worth noting that this research specifically studied college students, not elementary schoolers, and the advantage appears driven by deeper cognitive processing rather than anything magical about pen and paper.

Similarly, a separate meta-analysis on reading comprehension found that students who read on paper consistently understand and remember more than those who read on screens. The effect is particularly pronounced for younger readers and for longer, more complex texts. Digital reading tends to encourage skimming rather than deep engagement, and the infinite distractions available on any connected device make focused reading genuinely harder.

UNESCO’s landmark 2023 Global Education Monitoring Report reviewed the worldwide evidence and concluded that there is “little robust evidence” that digital technology adds value to education on its own. The report found a negative link between excessive device use and student performance, and it urged governments to regulate technology use in schools rather than embracing it uncritically. That is not a fringe position from a technophobic think tank. That is the United Nations’ education arm reviewing global data and raising a red flag.

None of this research says “Chromebooks are bad.” What it says is that screens can undermine learning when they replace rather than supplement traditional instruction, and that excessive, unstructured screen time correlates with worse outcomes. Those are different claims, and the distinction matters enormously.

The Test Score Question

Twenge’s most powerful weapon is the NAEP data. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, often called “the nation’s report card,” painted a devastating picture in 2024. Twelfth-graders hit historic lows in both math and reading, with 45 percent failing to demonstrate even basic math knowledge. Reading scores fell below 1992 levels. These are real numbers that should alarm everyone.

But here is where the narrative gets complicated. The decline in American test scores began around 2012, well before most schools adopted one-to-one Chromebook programs. The pandemic, which forced millions of students into isolation and disrupted two years of normal instruction, created a crater in learning outcomes that researchers are still trying to measure. Chronic absenteeism has reached unprecedented levels, with students simply not showing up to school at rates that dwarf pre-pandemic norms. Smartphones became ubiquitous among teenagers around the same time scores started sliding, introducing social media, short-form video, and constant notifications into the lives of developing brains.

Attributing the test score decline primarily to Chromebooks requires ignoring these confounding factors, and serious researchers are careful not to do so. That does not mean Chromebooks played no role. It means the honest answer is that we do not have causal evidence isolating school-issued devices as a primary driver of declining achievement. What we have is correlation alongside a dozen other plausible explanations, several of which have stronger evidence behind them.

Why Teachers Are Pushing Back

The teacher perspective is where this debate gets most interesting, because teachers are not dealing in abstractions. They are watching real students struggle with real devices every day. An Education Week survey found that 56 percent of educators say off-task behavior on laptops and tablets is a major source of distraction, ranking it above cellphones as a classroom problem. More than a quarter of students spend five or more hours daily on screens during class time. One teacher told Education Week she simply told her students to put their Chromebooks away for good, reverting to paper-based instruction entirely.

Daniel Buck, a former English teacher writing for the Fordham Institute, captured the frustration well. He describes watching students supposedly practicing math on educational software while actually playing online games. “Schools ban phones but allow access through one-to-one computing to many of the same diversions,” he writes. “Policy wonks might be unfamiliar with words such Slope, Dolphin Olympics, or Crazy Games, but these online games are a mainstay of modern classrooms.” His argument is that phone bans, while welcome, do not go far enough when students still have unrestricted laptops in front of them all day.

In Los Angeles, parents organized a campaign demanding that schools pull back on mandatory screen time after discovering their children were using school-issued devices to watch YouTube and play Fortnite during class. One parent reported that teachers acknowledged her son understood the material but simply could not stay on task with a screen in front of him. The district, which had spent heavily on devices during the pandemic, found itself facing the uncomfortable possibility that its technology investment was making some students’ problems worse.

These are not isolated anecdotes. They represent a growing consensus among the people who spend their days in classrooms: too many students are drowning in unstructured screen time, and the devices schools provided to help them learn are often doing the opposite.

What Devices Actually Enable When Used Well

Here is where I push back on the “Chromebooks have failed” narrative, because it ignores what these devices make possible when schools deploy them thoughtfully. The distinction matters, and it is not a minor one.

For millions of students from low-income families, the school-issued Chromebook is their only computer. It is how they access Google Classroom, connect with teachers outside school hours, and reach research materials that other students access from personal laptops at home. The equity question here is real and practical: if a district serving predominantly low-income students pulls its devices without a replacement plan, those students lose access to digital learning entirely. That does not make Chromebooks above criticism, but it does mean “just get rid of them” is not a serious policy position for schools where families cannot fill the gap themselves.

A Forrester study on Chromebook impact found that students gained 18 extra hours of instructional time per year from faster device startup and fewer technical interruptions, while teachers saved 42 hours annually on administrative tasks. Some districts reported double-digit growth in test scores after implementing Chromebook programs alongside structured Google Workspace for Education. I should note that this study was commissioned by Google, so you should weigh it accordingly, but the underlying data came from interviews with leaders at nine real school systems who reported measurable improvements.

The Chromebook vs. iPad debate for schools, which we have covered extensively, consistently comes down to affordability, manageability, and the physical keyboard. A complete Chromebook setup for school costs $250 to $350, including the keyboard, while a school-ready iPad runs $530 to $730 with necessary accessories. That price difference is not trivial when you are outfitting a district of thirty thousand students. And unlike phones or tablets, education Chromebooks are purpose-built for fleet management, with ruggedized designs, spill-resistant keyboards, and centralized administration tools that give IT departments genuine control over what students can access.

The Real Problem Is Not the Device

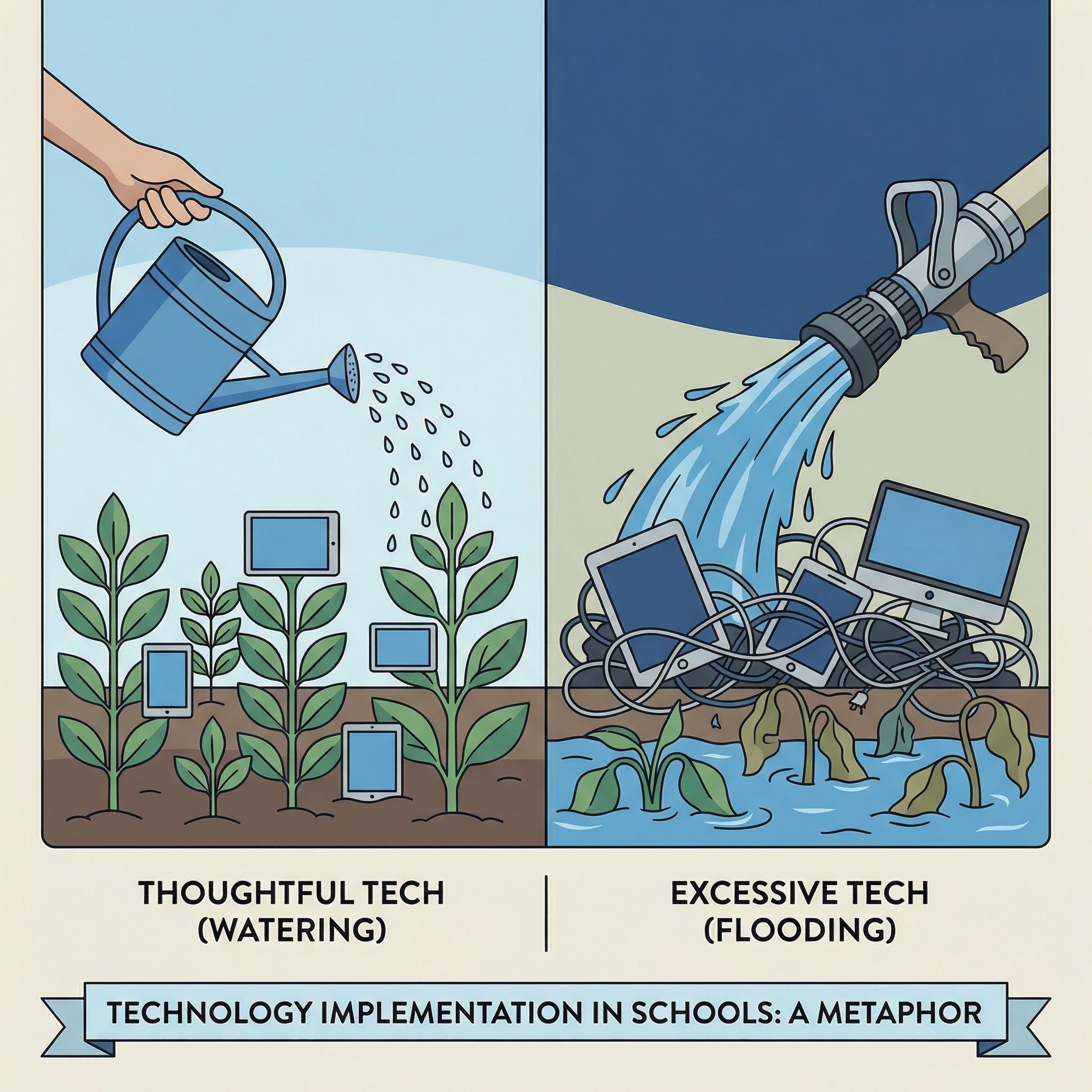

Daniel Buck offered an analogy in his Fordham piece that I think captures the situation perfectly: “Watering the grass can foster a healthy lawn; flooding the lawn can suffocate the grass.” The problem is not that schools gave students computers. The problem is that many schools gave students computers without a coherent plan for how to use them, when to use them, and crucially, when not to use them.

The UNESCO report’s most important finding was not that technology hurts learning. It was that technology helps as a supplement but hurts as a substitute for human instruction. Devices prove beneficial when they provide extra practice opportunities, enable collaboration, and support teachers. They prove harmful when they replace direct instruction, when students spend entire class periods clicking through educational software instead of engaging with a teacher and their peers, and when schools deploy them without adequate teacher training or device management policies.

Before the pandemic, about 40 percent of elementary schools provided devices to students. After the pandemic, that number leapt to 84 percent. Districts spent tens of millions in COVID relief dollars on devices, software, and licenses. But spending money on technology is not the same as implementing it well, and many schools simply handed out Chromebooks without rethinking their instructional approach, training teachers on device management, or establishing clear boundaries around when screens belong in the learning process and when they do not.

What Parents and Schools Can Actually Do

This is where the conversation needs to go, because “Chromebooks failed” is not actionable and “Chromebooks are fine” is not honest. Here is what the research, the teacher testimony, and the technology itself suggest as a path forward.

For younger students, lean heavily on paper. The research on handwriting and reading comprehension is strongest for elementary-aged children. Young students building foundational literacy and numeracy skills benefit from the physicality of writing letters, the focused attention that paper books demand, and the reduced distraction of an offline learning environment. This does not mean eliminating devices in lower grades, but it means reserving them for tasks where technology adds genuine value, such as a virtual field trip or an interactive science simulation, rather than digitizing worksheets for the sake of being digital.

For older students, teach intentional use. By middle and high school, digital literacy is a genuine career skill. Students need to learn how to research online, collaborate through shared documents, and create presentations and projects that reflect how modern workplaces function. The key is structured use with clear expectations, not all-day open access to a connected device. A reasonable model might look like specific class periods designated for device use, with Chromebooks closed or collected during instruction, discussion, and reading.

Use the management tools that already exist. Chrome OS offers more granular device management than any other education platform, and many schools barely scratch the surface of what is available. Through the Google Admin Console, administrators can restrict which websites and apps students can access, set time-of-day schedules that lock down devices during certain periods, push out classroom management tools that let teachers see and control student screens in real time, and enforce content filtering that goes well beyond simple blocklists. If your school’s Chromebooks feel like unmanaged distractions, the problem is likely configuration, not the device itself.

Parents should engage with Family Link. Google’s Family Link lets parents set screen time limits, approve or block apps and websites, set bedtime restrictions that disable the device, and monitor activity on school-issued Chromebooks during out-of-school hours. Many parents do not realize these controls exist or assume the school handles everything. Taking an active role in managing your child’s device use, especially at home, is one of the most immediate and effective steps you can take.

Ask your school the hard questions. What device management policies are in place? How much class time is spent on screens versus analog instruction? Are teachers trained on classroom management software like GoGuardian? Has the district established clear guidelines on when device use is and is not appropriate? Schools that have thoughtful answers to these questions tend to be the ones where Chromebook programs work well. Schools that respond vaguely are the ones where devices have become a problem.

The Nuance Nobody Wants to Hear

The uncomfortable truth is that both sides of this debate are partly right and partly wrong. Twenge is right that unstructured screen time hurts learning and that many schools deployed devices without adequate planning. She is wrong to characterize the entire concept of school-issued computing as a failure when the evidence shows clear benefits from well-implemented programs and when removing devices would disproportionately harm students who have no other access to technology.

The education technology industry is right that Chromebooks enable collaboration, equity, and administrative efficiency in ways that no paper-based system can match. They are wrong to downplay the growing body of evidence that too much screen time undermines the deep reading, handwriting, and focused attention that students desperately need to develop.

For parents navigating this debate, the most useful framing might be the simplest one. A Chromebook is a tool. Like any tool, its value depends entirely on how it is used. A hammer in the hands of a skilled carpenter builds houses. A hammer left unsupervised with a group of children is a liability. The answer is not to eliminate hammers. The answer is to make sure the people using them know what they are doing, and to put them away when they are not needed.

The 93 percent of US school districts planning to purchase Chromebooks in 2025 are not making a mistake. But the ones that hand them out without clear usage policies, teacher training, and device management are setting their students up for exactly the failure that Twenge describes. The research is clear enough to act on. Whether schools actually will is another question entirely.