The Self-Hosting Renaissance: Why 2026 Is Finally the Year Everyone's Running Their Own Server

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

Something shifted in the self-hosting world over the past year, and if you’ve been watching communities like r/selfhosted or r/homelab, you’ve probably noticed. The posts used to be dominated by experienced sysadmins sharing complex Kubernetes deployments and arguing about the finer points of ZFS. Now there’s a steady stream of excited newcomers posting their first successful Immich installations, asking beginner questions without getting roasted, and sharing photos of their compact home server setups. The self-hosting market is projected to reach $85.2 billion by 2034, growing at 18.5% annually, but what’s more interesting than the numbers is who’s driving that growth: regular people who never wanted to become sysadmins.

The conventional wisdom for the past decade was that self-hosting required either significant technical expertise or a willingness to spend weekends debugging configuration files. You needed to understand networking well enough to set up port forwarding, know enough Linux to troubleshoot when things broke at 2am, and have the patience to translate cryptic error messages into actionable fixes. For most people, even tech-savvy ones, the juice simply wasn’t worth the squeeze. Paying $10 a month for Google One was easier than learning how to run your own photo backup server.

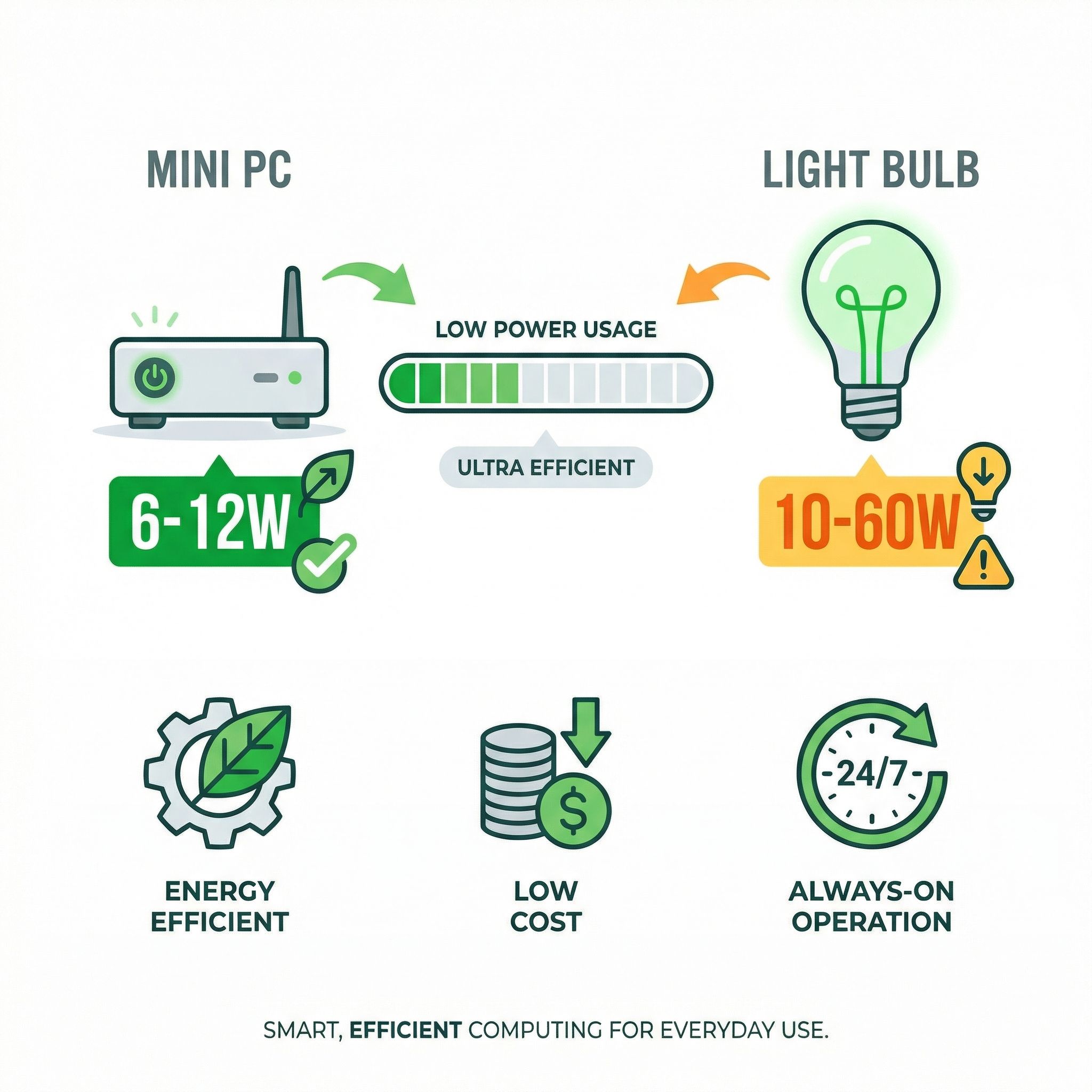

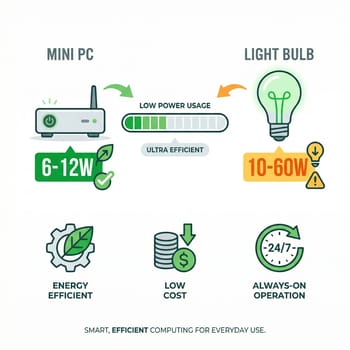

2026 is different, and it’s different for three specific reasons that happened to converge at the same time. The first is that AI assistants like Claude Code can now handle the configuration that used to require hours of documentation reading and forum searching. The second is that Intel’s N100 and N150 processors created a new category of mini PCs that are quiet, cheap, and sip just 6-12 watts while running a dozen containerized services. The third is that Tailscale eliminated the networking nightmare that scared off more potential self-hosters than any other single factor. Each of these developments would have made self-hosting easier on its own. Together, they’ve made it accessible to anyone who can follow instructions and isn’t afraid of a terminal window.

AI Assistants Killed Configuration Fatigue

The traditional self-hosting experience went something like this: you’d find an interesting service, spend an hour reading the documentation trying to understand the installation process, copy some commands into your terminal, hit an error, spend another hour searching forums for someone who encountered the same problem, try the suggested fix, hit a different error, and eventually either succeed through sheer persistence or give up and go back to the cloud service you were trying to replace. This cycle repeated for every new service you wanted to run, and the complexity compounded as you added more services that needed to interact with each other.

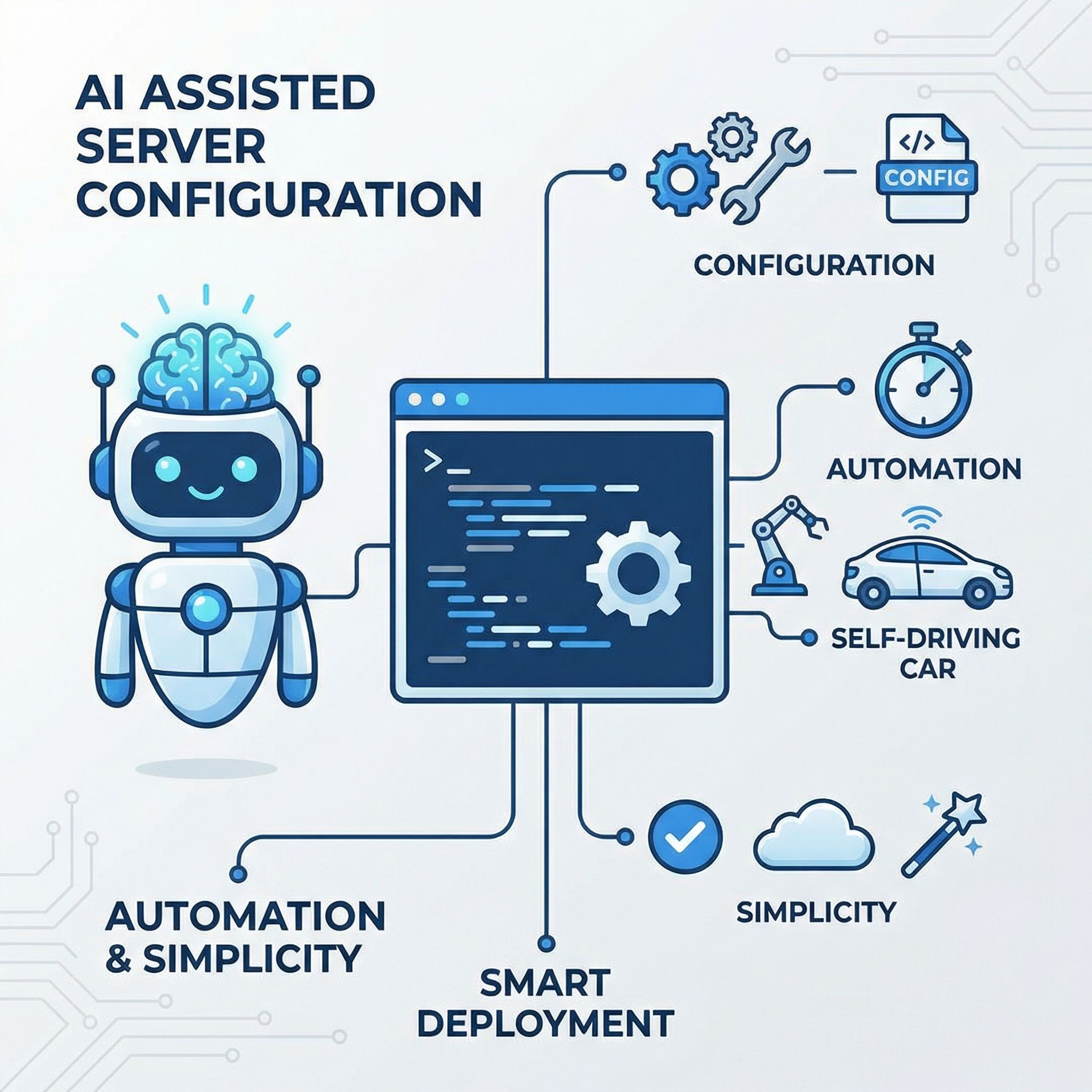

CLI agents like Claude Code have fundamentally changed this dynamic, and not in a theoretical “AI will eventually help with this” way, but in a practical “I can ask it to set up my home server right now” way. As one self-hosting evangelist put it, this is “the first time I would recommend it to normie/software-literate people who never really wanted to become a sysadmin and stress about uptime of core personal services.” The key insight is that the real innovation isn’t the hardware, which has been cheap for years. It’s that you no longer need to become a sysadmin to make it work.

When you ask an AI assistant to help you set up Docker, it doesn’t just give you commands to copy. It can examine your current system configuration, suggest appropriate container images, help you understand what each parameter does, and troubleshoot errors as they occur. The feedback loop that used to take hours of forum searching now takes seconds. More importantly, the AI can explain why something went wrong in a way that helps you learn, rather than just giving you the magic incantation to make the error go away. This means people actually understand their setups better than they did in the copy-paste-from-Stack-Overflow era.

The caveat here, and it’s worth being honest about, is that AI assistants aren’t magic. They get confused, hallucinate solutions that don’t work, and occasionally suggest configurations that are subtly wrong. The experience is “dramatically easier,” not “effortless.” But even with these limitations, the bar has lowered enough that reasonably tech-literate people, the kind who can follow instructions and aren’t scared of a terminal, can now get a home server running in an afternoon rather than a weekend.

The N100 Changed the Hardware Equation

Before Intel’s N100 processor and its successors, your home server options were essentially: run a full desktop PC that sounds like a jet engine and costs $50 a year in electricity, repurpose an old laptop with thermal management issues, or set up a Raspberry Pi that’s underpowered for anything beyond the basics. The N100 created a fourth option that hits a sweet spot most people didn’t know existed: 6-12 watts at idle, complete silence with fanless designs, and enough x86 processing power to run a dozen Docker containers without breaking a sweat.

The economics are compelling when you run the numbers. An Intel N100 mini PC typically consumes 9-12 watts with a dozen containers running, which translates to roughly $8-12 per year in electricity at US rates. Compare that to the cloud services you might replace: Google One for photos ($30/year for 200GB), a password manager subscription ($36/year), maybe Plex Pass ($120/lifetime or $5/month), cloud storage for backups ($100+/year depending on size). The mini PC pays for itself in saved subscriptions within the first year, and every year after that is pure savings.

The newer N150 offers about 6-10% better performance than the N100 while maintaining the same power efficiency, making it an even better choice for new builds. These processors support modern features like DDR5 memory and have integrated graphics capable enough for basic hardware transcoding, eliminating the need for a dedicated GPU in most home server scenarios. The combination of adequate performance, minimal power draw, and affordable pricing has made N100/N150 mini PCs the default recommendation in home lab communities.

GMKtec G3 Plus

- +Ultra-low power draw

- +2.5Gb Ethernet

- +silent operation

- +under $200

- -Intel N150 is modest for heavy workloads

- -limited upgrade options

For beginners, the choice is straightforward: pick up an N100 or N150 mini PC in the $150-250 range, install Proxmox or just run Docker on Ubuntu, and you’re ready to start. The BOSGAME B100 offers more storage expansion options for those who plan to grow their setup, while still maintaining the efficiency that makes 24/7 operation practical.

BOSGAME B100

- +Dual NVMe slots for expansion

- +32GB RAM

- +excellent build quality

- -Slightly larger form factor

- -no Thunderbolt

Tailscale Made Networking Trivial

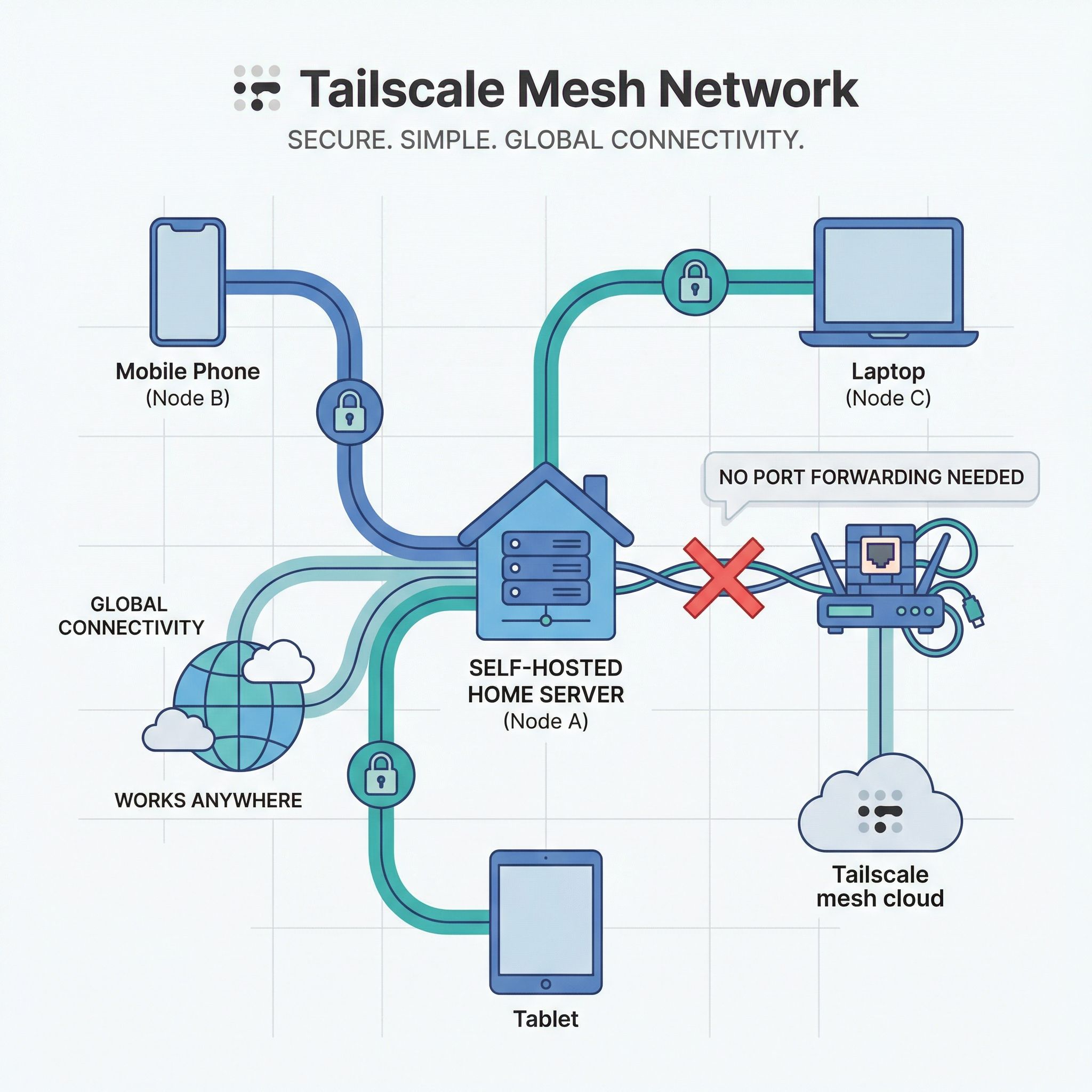

Ask anyone who abandoned a self-hosting project what finally killed their momentum, and there’s a good chance the answer involves networking. Setting up port forwarding on a residential router, dealing with dynamic IP addresses that change when you least expect it, configuring reverse proxies with SSL certificates, and figuring out how to safely expose services to the internet without creating a security nightmare, these are the challenges that stopped more self-hosting journeys than any other factor.

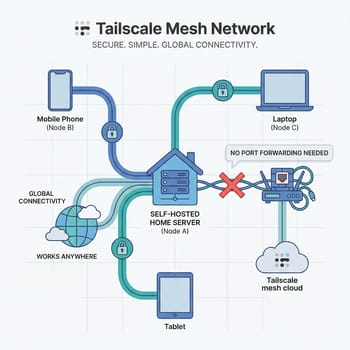

Tailscale solves essentially all of these problems by creating a private mesh network that works through NAT and firewalls automatically. No port forwarding required. No exposed services. No complex DNS configuration. You install the Tailscale client on your devices, join them to your network, and they can communicate with each other directly using WireGuard encryption, regardless of what ridiculous NAT situation your ISP or router has created. The free tier covers up to 100 devices, which is more than most home labs will ever need.

The experience of setting up remote access to a home server has gone from “spend a weekend learning about CGNAT, ddclient, nginx reverse proxies, and Let’s Encrypt certificates” to “install Tailscale on your server, install Tailscale on your phone, done.” When you’re on your tailnet, your home server is accessible as if you were on your local network, with the same simple URLs and without any of the security exposure that comes with opening ports to the public internet.

Tailscale’s MagicDNS feature adds automatic DNS names for every device on your network, so you can access your services at memorable addresses like homeserver.tailnet instead of IP addresses. They also provision TLS certificates automatically, securing your connections without any of the certificate renewal headaches that traditionally plagued self-hosted setups. For those who want to go deeper, Tailscale can act as a subnet router, letting you access your entire home network remotely, not just devices with Tailscale installed.

What People Are Actually Running

The 2026 homelab stack has crystallized around a few key applications that offer genuinely compelling alternatives to cloud services. Understanding what’s worth self-hosting, and what still isn’t, helps set realistic expectations for newcomers.

Immich has emerged as the default Google Photos replacement, offering automatic backup of phone photos with facial recognition, album sharing, and a polished mobile app that rivals the commercial alternatives. The setup is more involved than some simpler services, but AI assistants can walk you through it, and the result is a photo backup solution you own completely without monthly fees or storage caps beyond what your hard drives can hold.

Vaultwarden, the lightweight Bitwarden server implementation, gives you a self-hosted password manager that’s fully compatible with all the official Bitwarden clients. Your passwords never leave your network, and unlike the cloud-hosted version, you’re not dependent on someone else’s infrastructure staying online and secure.

Ollama has made running local language models trivially easy, and homelabbers are integrating AI into everything. Combined with Open WebUI, you get a ChatGPT-like interface running entirely on your hardware, with Tailscale Serve providing secure access from anywhere on your network, including phones and tablets.

Plex or Jellyfin for media streaming, Home Assistant for home automation, Nginx Proxy Manager or Caddy for reverse proxy and HTTPS, and Uptime Kuma for monitoring round out the typical stack. Users report running 14+ containerized services simultaneously on N100 hardware, with the tiny servers idling at under 10% CPU.

For those interested in local AI workloads beyond basic Ollama chat, a more powerful machine makes sense. The Beelink SER8 with its AMD Ryzen 7 processor can handle larger language models and multiple concurrent AI tasks that would overwhelm an N100.

Beelink SER8

- +AMD Ryzen 7 performance

- +excellent for local AI

- +multiple display outputs

- -Higher power consumption than N100

- -costs more upfront

The Realistic Limitations

Honesty about what self-hosting still struggles with is important for setting expectations. The mobile app experience for self-hosted services, while improving, generally lags behind polished commercial alternatives. Immich’s app is good, but it’s not quite Google Photos smooth. Paperless-ngx works, but it requires more manual intervention than commercial document management services.

Uptime is your responsibility. When your home internet goes down, or you accidentally break something during an update, your services go down with it. For services that truly matter, like password managers, having an offline fallback or a backup strategy becomes essential. Cloud services offer 99.9% uptime SLAs backed by professional operations teams. Your home server offers whatever reliability you can manage to engineer.

The maintenance burden after initial setup deserves consideration. AI assistants help tremendously with the setup phase, but ongoing updates, security patches, and troubleshooting when things break still require attention. You don’t need to be a sysadmin to run a home server in 2026, but you do need to be willing to spend a few hours a month on maintenance. Automatic updates can handle routine patches, but major version upgrades often require manual intervention, and the more services you run, the more maintenance surface area you create.

Backup and disaster recovery remain the hidden complexity that catches beginners off guard. Your mini PC’s NVMe drive will eventually fail, and when it does, you need a recovery plan. At minimum, this means regular backups to an external drive or cloud storage, tested restoration procedures, and documentation of your configuration. The MINISFORUM MS-01 offers serious expandability for those building more resilient setups with redundant storage.

MINISFORUM MS-01

- +Dual 10Gb Ethernet

- +NVMe RAID support

- +Thunderbolt 4

- -Premium pricing

- -overkill for basic setups

The Cost Comparison

The financial case for self-hosting depends heavily on what services you’re replacing and how many years you plan to run your server. A simple comparison helps illustrate the math:

Typical cloud subscription costs per year:

- Google One 200GB: $30

- Password manager: $36

- Cloud backup service: $100

- Photo storage beyond free tier: $50+

- VPN service: $60-100

- Total: $276-316/year

Self-hosting costs:

- N100/N150 mini PC: $150-250 (one-time)

- External backup drive: $100 (one-time)

- Electricity: $8-12/year

- Time investment: Your hourly rate varies

If you value your time at zero dollars, self-hosting pays for itself within the first year. Even if you account for the learning curve and ongoing maintenance, the second year onward is essentially pure savings versus cloud subscriptions. The math becomes more favorable the more services you consolidate, though it’s worth acknowledging that the comparison only works if you actually cancel the cloud subscriptions you’re replacing.

Getting Started in 2026

The on-ramp has never been smoother for those ready to try self-hosting. Pick up an N100 or N150 mini PC, install Proxmox or Ubuntu Server with Docker, set up Tailscale for remote access, and start with one or two services that solve real problems for you. Photo backup with Immich and password management with Vaultwarden are excellent first projects that offer immediate practical value.

Use an AI assistant to help with the setup, but don’t treat it as magic. Ask it to explain what each command does, not just to give you commands to copy. You’ll learn more and be better equipped to troubleshoot when something eventually goes wrong. Start small, add services gradually, and give yourself permission to break things. Your home lab is a learning environment, not a production data center.

The self-hosting renaissance of 2026 isn’t really about the technology, though the technology has finally caught up. It’s about regular people deciding they want more control over their data, their subscriptions, and their digital lives. The tools are ready. The community is welcoming. And for the first time, you don’t need to become a sysadmin to join in.