Snapdragon X2 ARM Mini PCs: The Fanless Future Is Almost Here

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

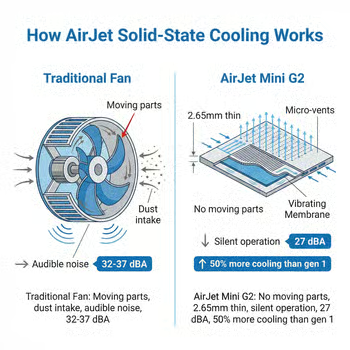

Qualcomm walked into CES 2026 with something that looked more like a drink coaster than a computer. The disc-shaped reference design, barely thicker than a stack of CDs, packed a Snapdragon X2 Elite Extreme chip with 18 CPU cores and no fans whatsoever. Instead of traditional blowers, it used Frore Systems’ AirJet solid-state cooling, a technology that moves air through tiny vents using vibrating piezoelectric membranes. No spinning parts, no noise, no dust intake. A second reference design fit inside a monitor stand, turning any display into a stealth all-in-one. Both were prototypes, not products you can buy today, but they represent the clearest vision yet of where ARM mini PCs are heading.

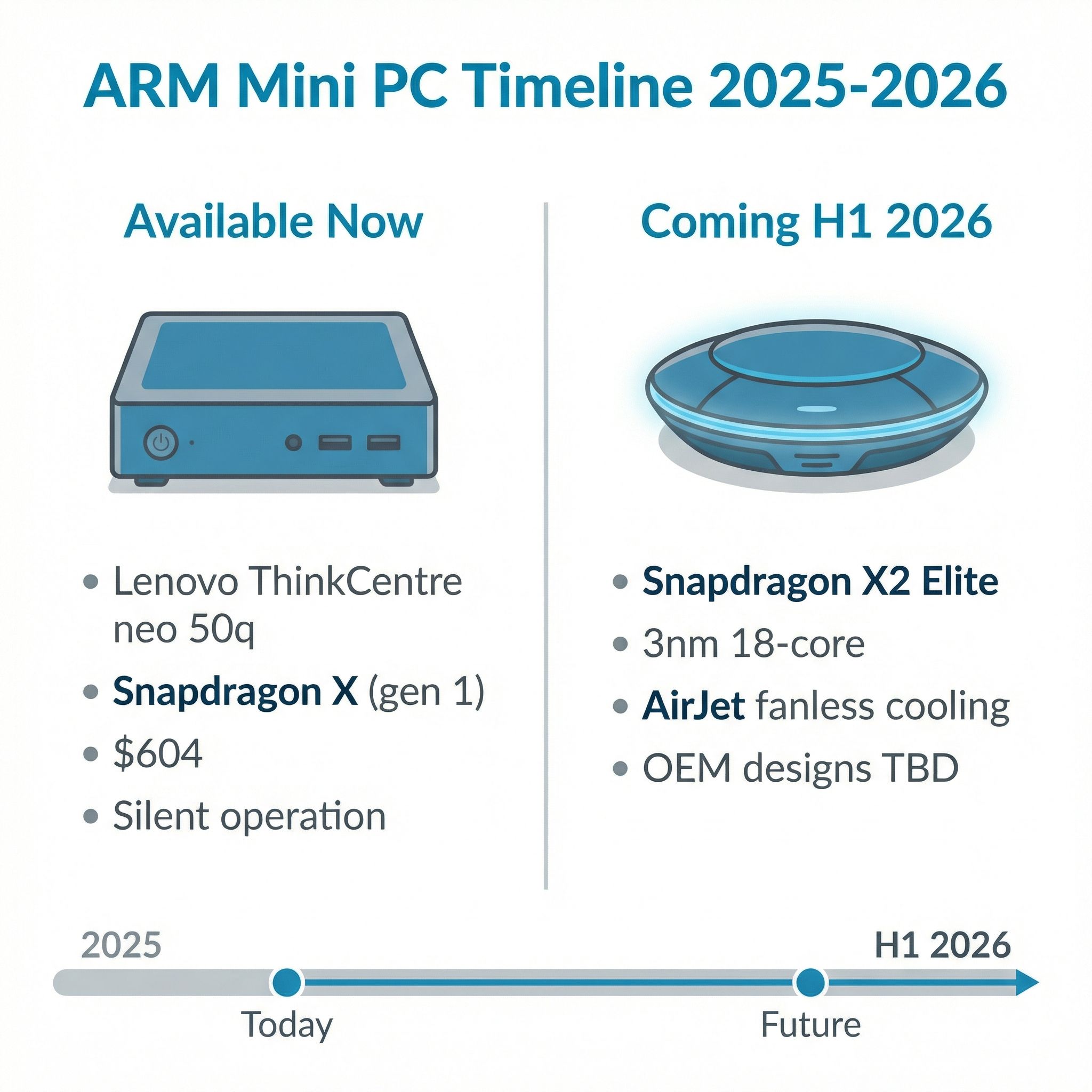

The timing matters. Microsoft released Windows 11 26H1 exclusively for ARM devices in February 2026, built on an entirely new codebase. The first ARM mini PC you can actually buy, Lenovo’s ThinkCentre neo 50q, has been shipping since late 2025 and earned strong reviews. And Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X2 Elite, built on TSMC’s 3nm process, is posting benchmark numbers that genuinely compete with Apple’s M5 in multi-threaded workloads. Something real is happening here, but the gap between prototype promise and daily-driver reality deserves honest examination.

What You Can Buy Today

The Lenovo ThinkCentre neo 50q is the only ARM-based Windows mini PC on the market right now, and it runs the original Snapdragon X, not the newer X2. At $604, it ships with 16GB of LPDDR5X RAM, a 1TB NVMe SSD, and a form factor small enough to VESA-mount behind a monitor. XDA’s review praised its silent operation, noting that the base Snapdragon X chip handles productivity tasks with surprising competence. The reviewer used it for weeks as a primary machine and didn’t miss their desktop tower much.

That $604 price deserves context, though. A capable fanless N100 mini PC runs $150-250, roughly a third of the Lenovo’s cost. The N100 sips 6 watts at idle and handles general productivity just fine. If all you need is a quiet desktop for browsing, documents, and light media consumption, the Intel option remains dramatically cheaper. The Snapdragon X earns its premium through genuinely stronger multi-threaded performance, a more capable NPU for on-device AI tasks, and an efficiency curve that scales better under sustained load. Whether that premium is worth it depends entirely on your workload.

The ThinkCentre neo 50q does have gaps worth noting. It’s a business-class machine from Lenovo, not the kind of budget-friendly hardware you’ll find from the mini PC brands that dominate this space, like Beelink, GMKtec, or MINISFORUM. None of those manufacturers have announced ARM-based models yet, though that may change once Snapdragon X2 silicon starts shipping to OEMs in volume. The neo 50q is also a first-generation product on a platform that’s still maturing, which brings us to the software question.

The App Compatibility Reality

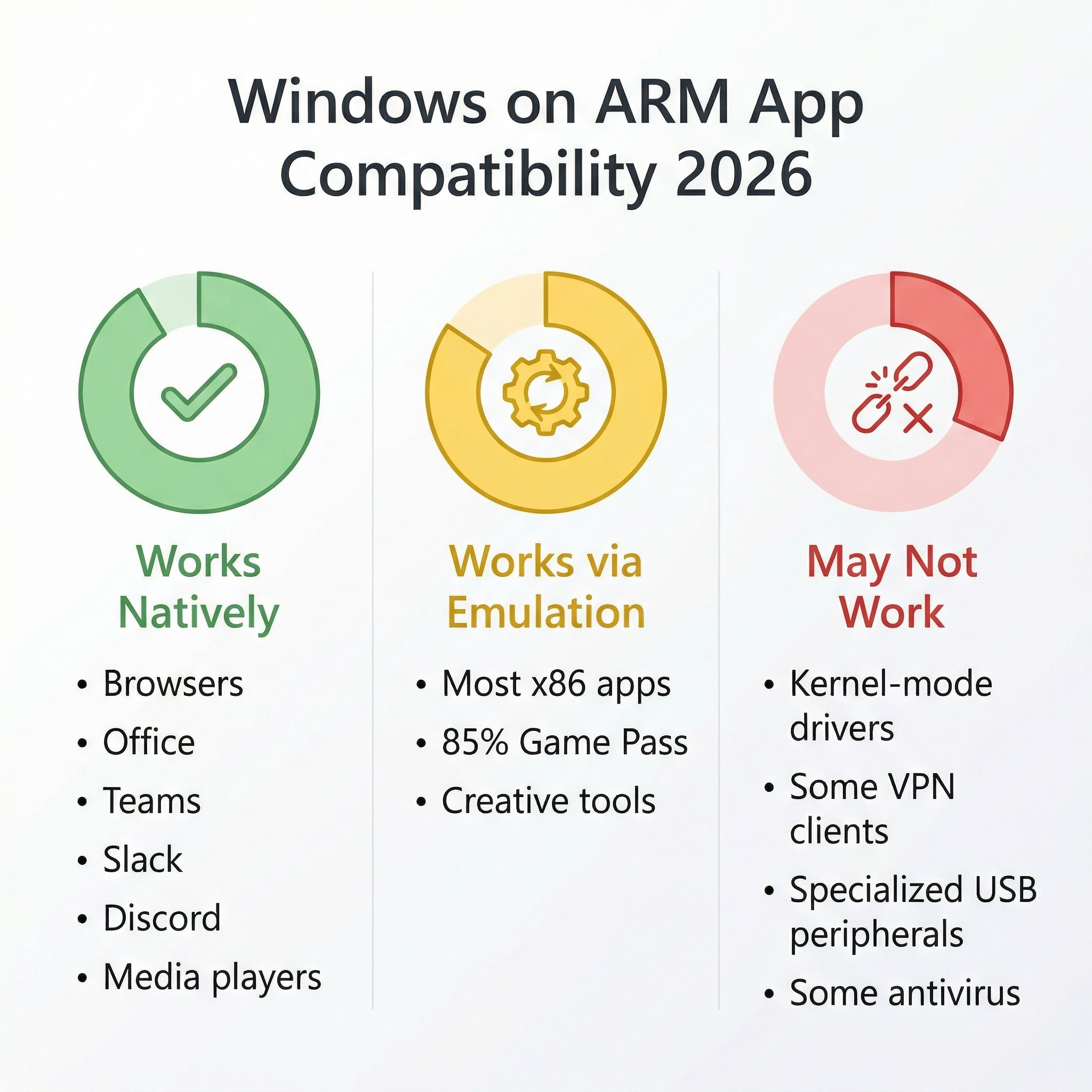

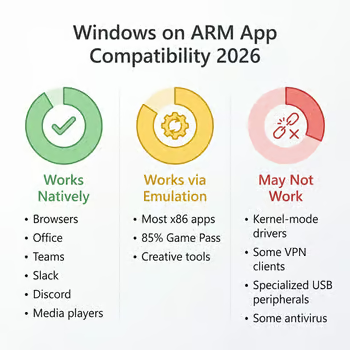

The single biggest concern people have about Windows on ARM is whether their software will actually work. The honest answer in early 2026 is: probably, with predictable exceptions. Microsoft’s Prism emulation layer translates x86 instructions to ARM64 code on the fly, and a major update in December 2025 added AVX and AVX2 support, dramatically expanding the list of compatible applications. Programs that previously refused to install, like Ableton Live 12, now run without issue.

For day-to-day productivity, the experience is nearly indistinguishable from an Intel machine. Browsers, Office apps, communication tools, media players, and most creative software work natively or through emulation that’s transparent enough that you won’t notice. One reviewer spent a full year using a Snapdragon device as a daily driver and concluded that most users won’t notice a meaningful difference between an Intel PC and a Snapdragon one. That tracks with what multiple reviewers have reported.

The exceptions follow a pattern. Adobe’s suite remains sluggish on ARM, a perennial complaint that’s improved but not resolved. Software that requires kernel-mode drivers, including certain antivirus programs, VPN clients, and specialized USB peripherals, may not work at all because Prism can’t translate kernel-level code. If you rely on a specific piece of hardware that needs custom Windows drivers, check ARM compatibility before buying. This is the most likely dealbreaker for enterprise users and anyone with a niche workflow involving proprietary peripherals.

Gaming has improved more than expected. Microsoft announced that the Xbox PC app now works on ARM devices and claims over 85% of the Game Pass catalog is compatible. Anti-cheat middleware from vendors like Easy Anti-Cheat has been ported to ARM, unblocking many multiplayer titles. Still, a mini PC buyer’s primary concern is typically productivity and media, not gaming, so this is more of a “nice to have” than a deciding factor.

The Snapdragon X2 Elite: What’s Coming

Qualcomm’s next-generation Snapdragon X2 Elite chips represent a serious generational leap. Built on TSMC’s 3nm process with third-generation Oryon CPU cores, the X2 Elite Extreme packs 18 cores in a big-medium-little configuration: 12 Prime cores clocking up to 5.0GHz for burst performance and 6 Performance cores at 3.6GHz for efficiency. That’s backed by 53MB of cache and an 80 TOPS neural processing unit that dwarfs anything Intel or AMD currently offers for on-device AI.

The benchmark numbers are genuinely impressive. Early Geekbench 6 multi-core scores landed around 23,000, comfortably beating Apple’s M5 (~17,800) and Intel’s Core Ultra 9 in multi-threaded workloads. Qualcomm claims the X2 architecture delivers up to 25% more multi-threaded performance while consuming significantly less power than the first-generation X Elite. The caveat: these numbers come from Qualcomm reference hardware under controlled conditions with pre-production software. Real-world OEM products will likely perform differently, as they always do.

Where Qualcomm still trails is single-core performance and GPU throughput. Apple’s M5 remains faster for the snappy, single-threaded tasks that make a computer feel responsive, like launching apps and scrolling web pages. The Adreno GPU in the X2 trails Apple’s M4 Pro by roughly 45% in synthetic graphics benchmarks. For a productivity-focused mini PC, that GPU gap matters less than it would for a gaming laptop, but it’s worth knowing.

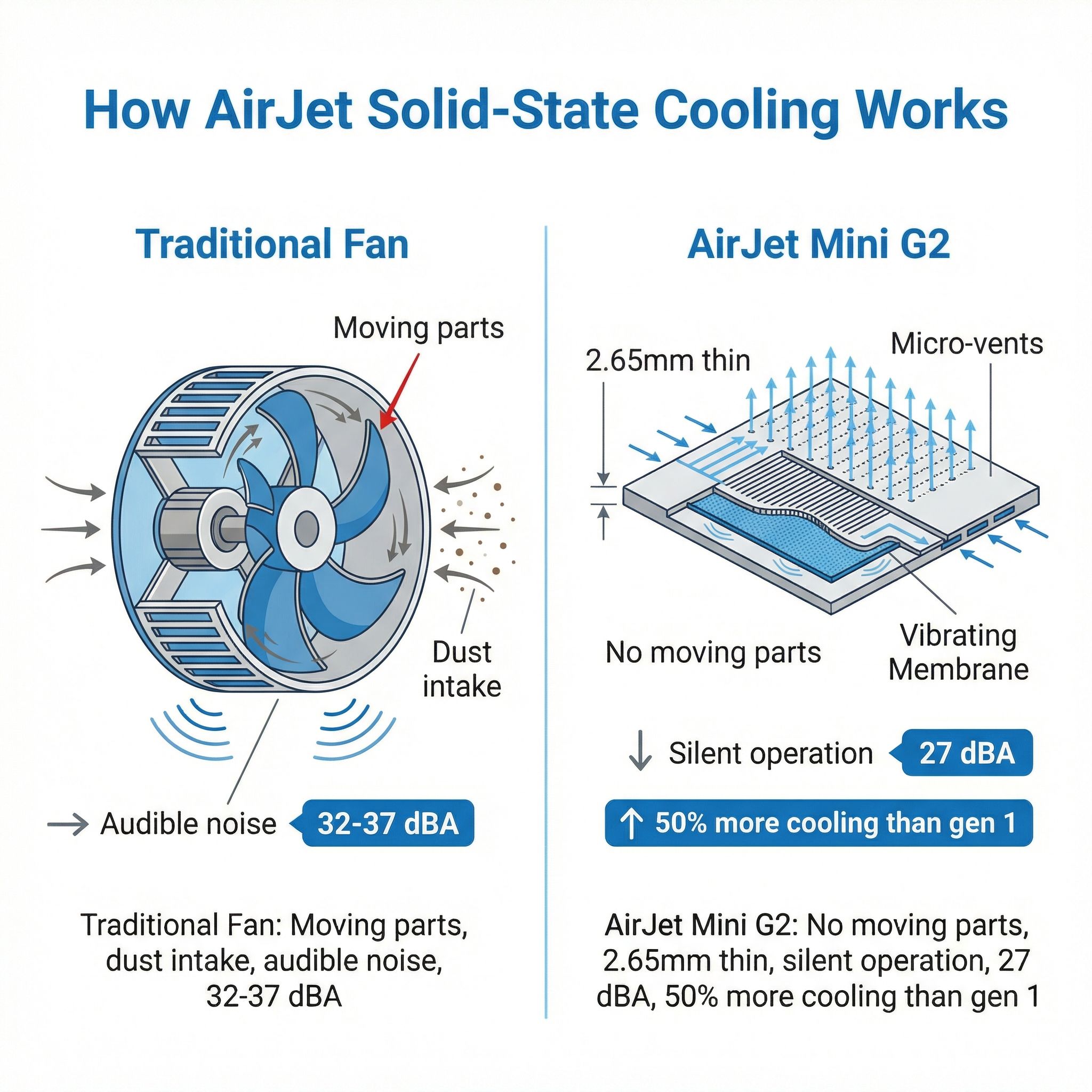

Solid-State Cooling: How AirJet Actually Works

The most visually striking aspect of Qualcomm’s CES reference designs wasn’t the processor but the cooling. Frore Systems’ AirJet Mini G2 is a solid-state active cooling chip measuring just 2.65mm thin. Instead of a fan blade spinning on a bearing, it uses piezoelectric membranes that vibrate at ultrasonic frequencies, pulling air across a heat exchanger and pushing it out through micro-vents. The result is active cooling with no moving parts, no audible noise, and no dust ingestion.

The second-generation AirJet Mini G2 removes 50% more heat than the original while maintaining the same ultra-compact footprint. In a Samsung Galaxy Book proof-of-concept at CES 2025, four AirJet Mini units replaced a dual-fan cooling system entirely. Cinebench tests showed the AirJet-cooled laptop actually ran faster than the fan-cooled version because the processor could sustain higher clocks without thermal throttling, all while running near-silently.

The technology has real limitations. A single AirJet Mini G2 handles modest thermal loads, appropriate for ultrabooks and thin mini PCs, but high-performance desktop chips generate more heat than solid-state cooling can currently manage. Frore’s AirJet Pak, which bundles multiple Mini G2 units together, can cool up to around 45 watts in a compact form factor. That’s enough for a Snapdragon X2 running within its efficient operating range, but not enough for a desktop-class AMD or Intel chip under sustained all-core load. This is precisely why ARM’s efficiency advantage matters for fanless designs: the X2 delivers strong performance at power levels that solid-state cooling can actually handle.

The first commercially available AirJet mini PC, Zotac’s ZBOX PI430AJ, shipped with an Intel Core i3 and two AirJet Mini chips. It’s the size of a deck of cards and runs completely silent. It proved the concept works in a real product, though with a modest processor. Qualcomm’s reference designs suggest the next generation will pair AirJet with much more capable silicon.

Microsoft’s ARM Bet Gets Serious

Microsoft’s decision to release Windows 11 26H1 exclusively for ARM devices sends an unmistakable signal about the company’s platform priorities. This isn’t a backport or a compatibility layer. It’s a separate Windows build on a new codebase, internally called “Bromine,” designed from the ground up for ARM silicon. Snapdragon X2 devices shipping in the first half of 2026 will run 26H1, while existing AMD and Intel machines continue on the separate 25H2/26H2 track.

The commitment is real, but so is the buyer risk. Devices running 26H1 are on an isolated servicing lane with no upgrade path to 26H2 when it arrives later this year. Microsoft has indicated these builds won’t converge until a future release, potentially not until the second half of 2027. For a mini PC buyer spending $600 or more, that means living on a separate Windows branch for over a year, potentially missing features and optimizations that ship in 26H2. Microsoft’s track record with the famously buggy 24H2 launch is the stated reason for this separation, and the caution is understandable, but it creates genuine uncertainty for early adopters.

The strategic read is that Microsoft sees ARM as central to Windows’ future, not just an alternative. A separate ARM-first codebase means Microsoft’s engineers are building for ARM as a primary target rather than retrofitting x86 features. Combined with Qualcomm’s performance improvements and the growing list of native ARM64 applications, the platform is approaching a tipping point. But approaching and reaching are different things, and first-half 2026 still feels like early-adopter territory.

The Linux Question

If you’re a mini PC enthusiast who runs Linux, ARM Windows desktops present an uncomfortable gap. The Lenovo ThinkCentre neo 50q’s Snapdragon X chip has limited Linux support, and running a standard Linux distribution on it ranges from difficult to impossible depending on the distro. Qualcomm’s Linux driver support has historically lagged behind their Windows efforts, and while progress is being made upstream in the Linux kernel, the experience is nowhere near the “install and go” simplicity of running Linux on an x86 mini PC.

This matters for Starryhope’s audience because many mini PC buyers run Linux for self-hosting, home automation, or simply as their preferred desktop environment. If Linux is part of your workflow, x86 mini PCs remain the practical choice for the foreseeable future. ARM Linux on desktop hardware will get there eventually, but right now the driver and compatibility work simply isn’t done. This is one area where Chromebooks, which run on ARM processors with Google-managed Linux support, have a meaningful head start over the Windows ARM ecosystem.

Who Should Care Right Now

The ARM mini PC landscape in early 2026 divides cleanly into three groups. If you’re a productivity-focused user who works primarily in a browser, Microsoft Office, and standard communication tools, and you value absolute silence, the Lenovo ThinkCentre neo 50q is a legitimate option today. It’s overpriced compared to N100 alternatives for basic tasks, but the combination of ARM efficiency, complete silence, and capable performance makes it genuinely appealing for desk-bound office work.

If you’re intrigued by the fanless disc-shaped designs and Snapdragon X2’s performance, the honest advice is to wait. Those are reference designs, not shipping products, and OEMs may or may not produce anything resembling them. Qualcomm expects X2-based systems to ship in the first half of 2026, but initial products will likely be laptops, not mini PCs. Give the OEM ecosystem six to twelve months to produce desktop-oriented X2 hardware, and give the software ecosystem time to build out native ARM64 support.

If you need Linux, if you rely on specialized peripherals with x86-only drivers, or if your budget is under $300, the mini PC world you already know, powered by Intel’s N100/N150 or AMD’s budget Ryzen chips, remains the better choice. Check out the mini PC comparison chart to find the right x86 option. ARM’s efficiency advantage is real, but the x86 ecosystem’s maturity, software compatibility, and price-to-performance ratio at the low end remain formidable.

The broader trend, though, is undeniable. ARM processors are getting faster at lower power, solid-state cooling is eliminating the last mechanical component from computers, and Microsoft is investing real engineering resources in making Windows on ARM a first-class platform. The disc-shaped puck Qualcomm showed at CES might not be available by summer, but it represents a future where your desktop computer is silent, draws less power than a light bulb, and fits in a coat pocket. For mini PC enthusiasts, that future is worth paying attention to, even if the smartest move today is to watch and wait.