The DGX Spark and the Reality of Local AI Hardware in 2026

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

When Jensen Huang unveiled Project DIGITS at CES 2025, now officially the DGX Spark, NVIDIA promised to “put a Grace Blackwell supercomputer on every desk.” The marketing materials are impressive: 128GB of unified memory, the company’s latest Blackwell GPU architecture, and up to one petaflop of AI performance for $3,999. After a year of real-world testing and independent benchmarks, we have a much clearer picture of what the DGX Spark actually delivers, and more importantly, who should care about this new category of dedicated AI hardware.

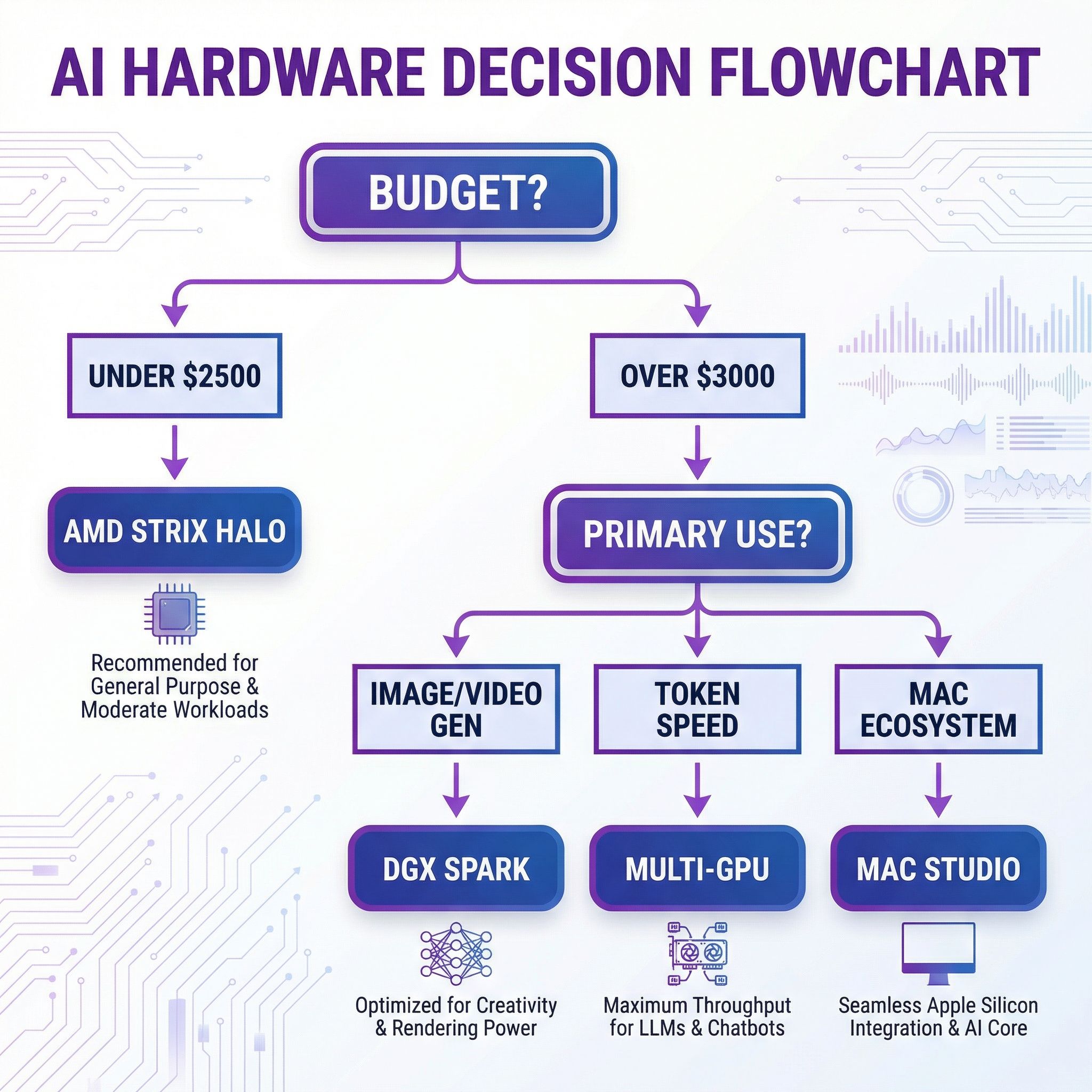

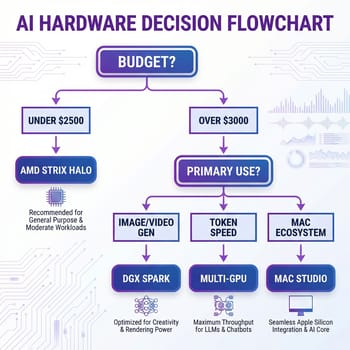

The honest answer isn’t simple, and understanding why requires looking beyond the spec sheet. For certain specific workloads, the DGX Spark offers capabilities you genuinely can’t get elsewhere at this price point. For others, a $1,500 multi-GPU setup or a $2,100 AMD alternative will significantly outperform it. And for many users experimenting with local LLMs, a high-end mini PC like the Minisforum AI X1 Pro or GEEKOM A9 Max can handle 13B-70B models at a fraction of the cost. Understanding which category your needs fall into requires digging past the marketing into the benchmark data, and that data tells a surprising story about what actually matters for local AI work.

The Bandwidth Bottleneck Nobody Talks About

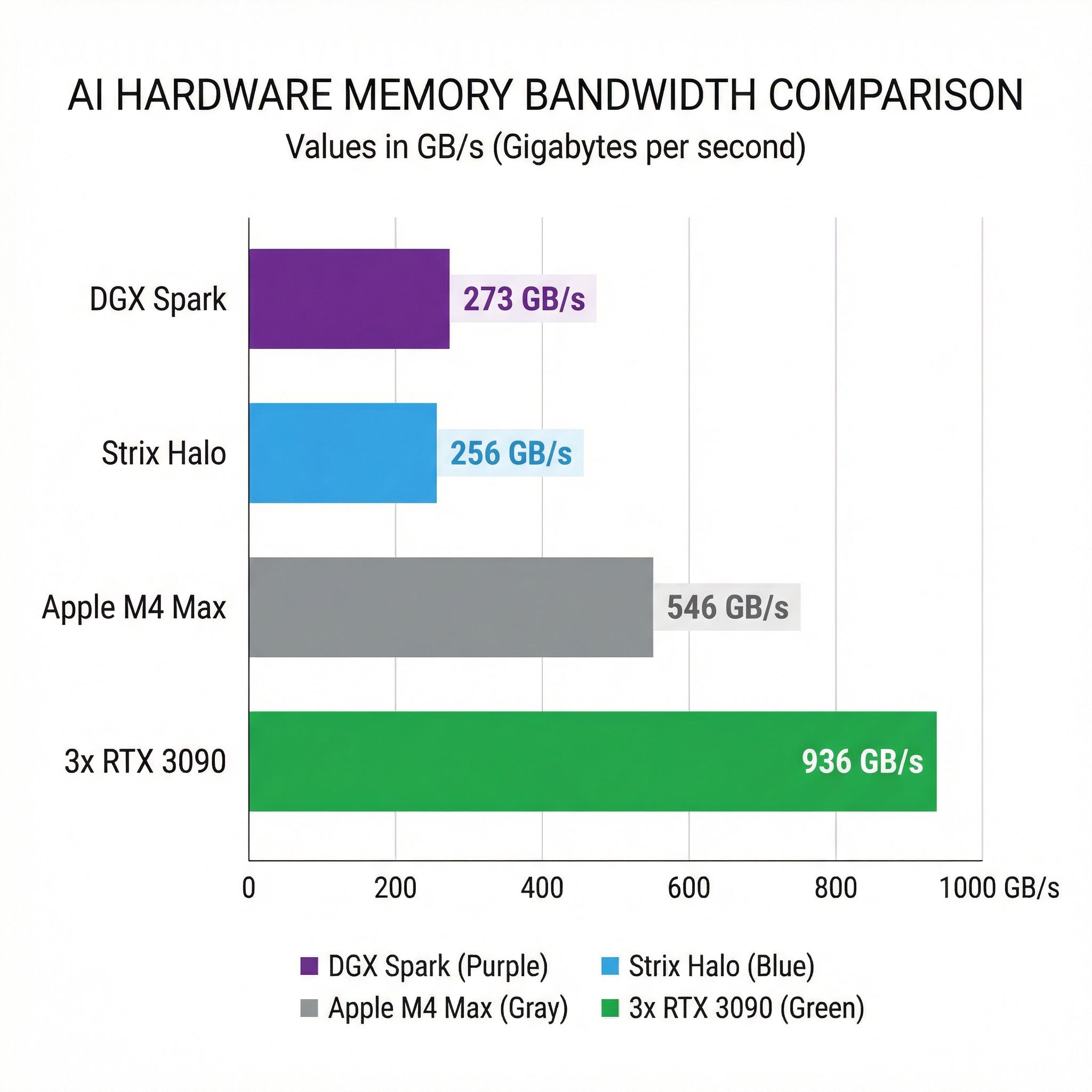

NVIDIA’s headline spec for the DGX Spark is 128GB of unified memory, and for running large language models locally, memory capacity matters enormously. A 70-billion parameter model requires roughly 140GB in FP16 precision, which means it simply won’t fit on most consumer hardware. The DGX Spark can load these models entirely into memory, which sounds like a clear win. But there’s a crucial spec that doesn’t make the marketing materials: memory bandwidth of 273 GB/s.

Memory bandwidth determines how quickly data moves from memory to the compute units, and for LLM inference, this number directly controls your tokens-per-second output. The DGX Spark’s 273 GB/s bandwidth places it marginally above AMD’s Strix Halo solution at 256 GB/s, while costing nearly twice as much. More striking is the comparison to Apple’s M4 Max, which offers 546 GB/s, essentially double the bandwidth at a similar price point for a Mac Studio configuration.

The real-world impact shows up clearly in benchmark testing by The Register. In single-batch token generation using Llama.cpp, AMD’s Strix Halo achieves a “narrow lead” over the DGX Spark when using the Vulkan backend. Both systems clock in around 34-38 tokens per second on a 120-billion parameter model. That’s respectably fast for local inference, but it means NVIDIA’s premium pricing isn’t buying you faster text generation for conversational AI use cases.

Where the DGX Spark does pull ahead is in time-to-first-token, the delay before responses start appearing. The Spark delivers roughly 2-3x better performance on this metric compared to Strix Halo, particularly with longer input prompts. For workflows involving large context windows or batch document processing, this advantage matters. But for the typical chatbot use case where you’re asking questions one at a time, the Strix Halo’s slower startup is barely noticeable while its token generation keeps pace.

The Multi-GPU Elephant in the Room

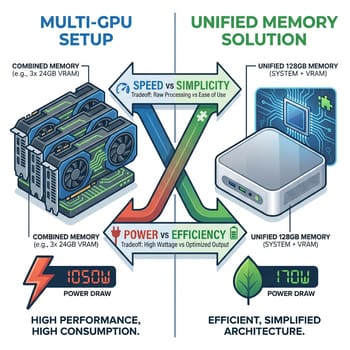

If raw token generation speed matters for your workflow, the benchmark data points to an uncomfortable truth for NVIDIA’s unified memory strategy. A DIY setup with three RTX 3090 GPUs achieves 124 tokens per second on the same 120B model where the DGX Spark manages 38 tokens per second. That’s 3.2x faster output for roughly the same total cost once you factor in a compatible motherboard and power supply.

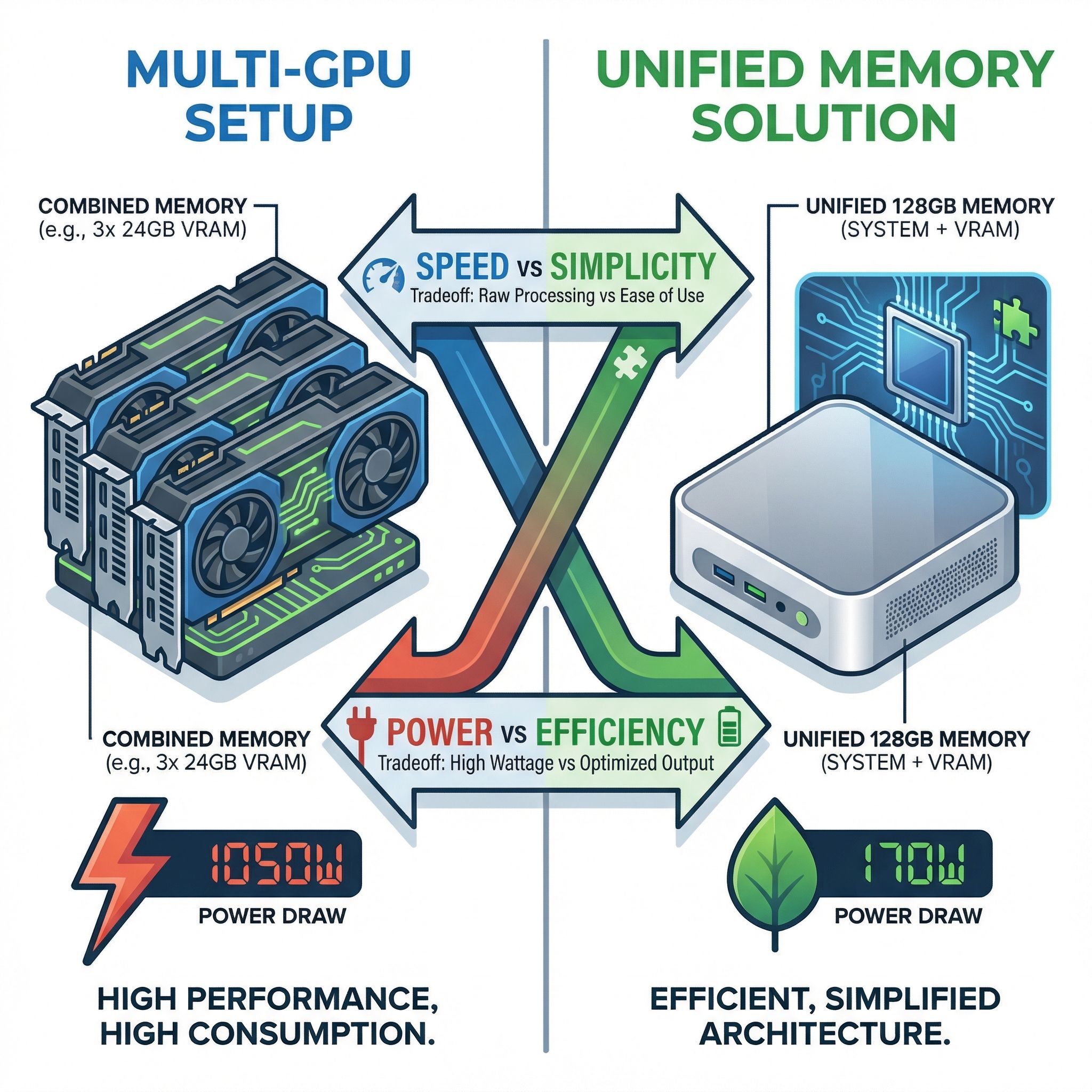

The math makes sense when you look at the bandwidth numbers. Three RTX 3090s aggregate to approximately 936 GB/s of memory bandwidth, more than triple the DGX Spark’s 273 GB/s. The trade-off is 72GB of total VRAM split across three cards, which means larger models need to be split across GPUs with some overhead, and the whole setup draws over 1,000 watts under load compared to the Spark’s 170W. You also need the space, the cooling, and the tolerance for a system that sounds like a small aircraft during inference.

The multi-GPU path isn’t for everyone, and that’s precisely NVIDIA’s pitch for the DGX Spark. It’s a turnkey solution that sits quietly on your desk, runs Ubuntu-based DGX OS out of the box, and doesn’t require you to become a systems integrator to get running. For professionals whose time has significant monetary value, the simplicity premium makes sense. For hobbyists who enjoy the tinkering, the multi-GPU route offers substantially better price-to-performance with the caveat that you’re signing up for ongoing maintenance complexity.

The used GPU market makes this comparison even more stark. Two RTX 3090s can often be found for under $1,500 total, and they’ll outperform the DGX Spark on pure token throughput while costing less than half as much. The calculus shifts if you need to run models above 72GB, but for the 70B-and-below range that covers most practical local LLM use cases, the DIY approach remains compelling for budget-conscious builders.

Where the DGX Spark Actually Wins

The benchmarks aren’t uniformly unfavorable for NVIDIA’s entry. In prompt processing, which measures how quickly the system can ingest and understand large input contexts, the DGX Spark matches or slightly beats the 3x RTX 3090 setup at around 1,700 tokens per second. The Blackwell architecture’s fifth-generation Tensor Cores and support for NVIDIA’s FP4 quantization format deliver real advantages for this compute-bound phase of inference.

Image generation tells an even clearer story. Testing with FLUX.1 Dev shows the DGX Spark generating images roughly 2.5x faster than AMD’s Strix Halo, pushing around 120 TFLOPS compared to the AMD’s 46 TFLOPS in similar workloads. If your workflow involves significant diffusion model usage, whether that’s Stable Diffusion, FLUX, or video generation models, the DGX Spark’s CUDA acceleration immediately justifies the price premium over AMD alternatives.

Fine-tuning performance is similarly strong. Full fine-tuning of Llama 3.2 3B completes in about two-thirds the time required by a comparable Strix Halo system, and QLoRA fine-tuning of Llama 3.1 70B shows an even larger gap: around 20 minutes on the Spark versus over 50 minutes on AMD. For AI researchers and developers who spend significant time training or fine-tuning models, these productivity gains compound quickly.

The software ecosystem advantage remains substantial, though it’s harder to quantify in benchmarks. The DGX Spark runs NVIDIA’s full CUDA stack with pre-installed NeMo, RAPIDS, PyTorch, and access to the NGC catalog. Most AI frameworks and models are optimized first for CUDA and often exclusively. AMD’s ROCm stack has improved dramatically but still lacks the ecosystem depth that CUDA provides. If you need to run cutting-edge models the week they’re released, you’ll hit fewer compatibility issues on NVIDIA hardware.

The AMD Alternative: Strix Halo

AMD’s Ryzen AI MAX+ 395 processor, the chip behind the Strix Halo platform, emerged as the DGX Spark’s most direct competitor. The Framework Desktop with 128GB RAM costs approximately $2,100, while HP’s Z2 Mini G1a runs around $2,950. Both configurations offer identical 128GB unified memory to the DGX Spark at a significant discount.

The performance tradeoffs are surprisingly favorable for AMD on many workloads. Token generation speeds land within 10% of the DGX Spark in most tests, meaning day-to-day chatbot interactions feel essentially identical. The Strix Halo falls behind significantly on time-to-first-token and prompt processing, which matters for workflows involving large documents or code analysis, but not for conversational AI use cases.

The larger practical advantage for AMD is flexibility. Strix Halo systems run standard Windows or Linux distributions rather than NVIDIA’s specialized DGX OS. You can use the same machine for general computing, gaming, or other tasks when you’re not running AI workloads. The DGX Spark, by contrast, is purpose-built for AI development and significantly restricted in versatility compared to a conventional desktop.

For budget-conscious developers who primarily need to run existing models for inference rather than training or fine-tuning custom models, Strix Halo offers roughly 90% of the capability at 55% of the cost. Even more affordable AMD-based mini PCs like the Beelink SER9 can handle smaller models (7B-13B) effectively for basic local AI experimentation. The ROCm ecosystem is “improving rapidly but still lacks the ecosystem depth” of CUDA, so you may encounter occasional compatibility friction with new models or frameworks, but for established workflows using popular models, the experience is increasingly comparable.

The Apple Question

Apple’s Mac Studio deserves mention in this comparison, particularly for developers already embedded in the Apple ecosystem. The M3 Ultra configuration offers up to 512GB of unified memory and 819 GB/s bandwidth, substantially outperforming the DGX Spark on memory-bandwidth-bound inference tasks. Independent testing shows 3x faster token generation for the Mac Studio on models that fit within its memory capacity.

The catch is pricing. A Mac Studio with M3 Ultra and substantial memory starts around $5,000 and scales up to nearly $10,000 for maxed configurations. You’re paying a significant premium for Apple’s vertical integration, but you’re also getting a general-purpose workstation that excels at video editing, software development, and other professional tasks beyond AI work.

For Mac developers specifically, there’s an interesting hybrid strategy emerging. Pairing a DGX Spark with a Mac Studio can achieve a 2.8x overall speedup compared to either system alone, with the Mac handling inference and the Spark handling training and fine-tuning. This setup makes the most of each platform’s strengths while avoiding the need to choose a single ecosystem for all AI work.

The FP4 Precision Question

NVIDIA’s claimed “one petaflop of AI performance” deserves scrutiny because it relies on FP4 precision, a new quantization format that packs more operations per memory access at the cost of numerical precision. Research shows FP4 quantization introduces roughly 2% accuracy degradation compared to higher precision formats, with the impact concentrated in tasks requiring precise reasoning like code generation and mathematical computation.

For casual conversational AI use, 2% accuracy loss is effectively invisible. For professional code assistance or scientific computing, it may matter significantly. The good news is that the DGX Spark supports multiple precision formats, so you can trade performance for accuracy as needed. The bad news is that the headline performance numbers assume you’re running everything at maximum compression.

The CES 2026 software updates NVIDIA announced tell a similar story. The claimed 2.5x performance improvement for Qwen-235B comes specifically from running the model with NVFP4 quantization, not from hardware improvements. These gains are real but model-specific, and they assume you’re willing to accept the precision tradeoffs that come with aggressive quantization. Marketing claims about AI hardware require reading the footnotes.

Who Should Actually Buy This

After a year of benchmarks and real-world reports, the DGX Spark’s ideal user profile has become clearer. The device makes the most sense for AI developers who prioritize compatibility and convenience above raw performance. These users typically need CUDA without spending hours on configuration, and their workflows lean heavily on prompt processing or batch operations rather than real-time chat. They’re also doing real development work with fine-tuning models and training custom variants, not just running inference on existing models. The turnkey experience matters more to them than squeezing every last dollar of value from their hardware budget.

The alternative paths serve different priorities. Conversational AI chatbots care more about token generation speed, where the DGX Spark’s bandwidth limitations become a bottleneck. Budget-conscious developers willing to build and maintain a multi-GPU setup will get significantly more performance per dollar, though they’re trading simplicity for complexity. Developers who need a general-purpose workstation that also handles AI work will find Strix Halo’s flexibility more practical, since it runs standard operating systems and can serve double duty as a regular desktop. And if image generation or creative AI work isn’t a priority in your workflow, AMD’s lower price tag makes the CUDA ecosystem premium harder to justify based on features you won’t use.

The broader question of whether anyone needs dedicated AI hardware at this price point depends entirely on their specific workflow. For most people experimenting with local LLMs casually, a gaming GPU they already own or a modest Strix Halo system will handle everything they need. The DGX Spark occupies a niche between consumer hardware that’s adequate for hobbyists and cloud compute that’s essential for serious production workloads. That niche exists, but it’s narrower than NVIDIA’s marketing suggests.

The Bigger Picture

The DGX Spark represents NVIDIA’s bet that a meaningful market exists for desktop-class AI workstations between consumer GPUs and cloud compute. A year into availability, the evidence is mixed. The hardware delivers on its core promise of running large models locally with reasonable performance, but the competition, both from AMD’s unified memory approach and from DIY multi-GPU setups, is more capable than NVIDIA’s premium pricing implies.

The more interesting observation is that this hardware category exists at all. Three years ago, running a 200-billion parameter model locally required enterprise-class equipment costing tens of thousands of dollars. Today, several options under $5,000 can accomplish the same task, with tradeoffs in performance, power consumption, and ecosystem maturity. The trajectory matters more than any single product comparison.

For developers and researchers following this space, the practical advice is to wait if you can. The competition between NVIDIA, AMD, and Apple in this segment is driving rapid improvement. Whatever you buy today will likely be outperformed at the same price point within 18 months. If you need the capability now, choose based on your specific workload profile rather than headline specs. The benchmark data consistently shows that there’s no single “best” option, only the best option for how you plan to use the hardware.

And if you’re considering the DGX Spark specifically, run your own benchmarks before committing. NVIDIA’s marketing emphasizes prompt processing and training workloads where the device genuinely excels. Independent testing consistently shows that token generation speed, the metric that matters most for interactive AI use cases, is where the premium pricing is hardest to justify. Your mileage will vary based on your actual workflow, which is exactly the kind of nuanced conclusion that doesn’t fit on a spec sheet.