Windows 11 SE Dies in October: What Microsoft Got Wrong and What It Means for ChromeOS

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

A disclosure before we begin: Starryhope covers Chromebooks extensively and has a natural interest in ChromeOS being seen favorably. What follows is our honest reading of Microsoft’s decision to end Windows 11 SE, including the parts where ChromeOS has its own problems. We think you deserve analysis, not cheerleading.

Microsoft did not hold a press conference. There was no blog post, no formal announcement, no mea culpa from a senior executive. In 2025, someone at Redmond quietly updated the Windows 11 SE FAQ page to inform schools that support would end in October 2026. “Microsoft will not release a feature update after Windows 11 SE, version 24H2,” the updated page read, recommending users “transition to a device that supports another edition of Windows 11 to ensure continued support and security.” And with that, Microsoft’s latest attempt to challenge ChromeOS in the classroom was over.

The quiet exit is perhaps the most telling detail. When Microsoft launched Windows 11 SE in late 2021, it did so with considerable fanfare, positioning it as a “purpose-built” cloud-first operating system designed for K-8 classrooms. By 2022, executives were calling it the start of a “new era of the PC.” Four years later, that era ended not with a bang but with a FAQ update.

What Windows 11 SE Actually Was

To understand why Windows 11 SE failed, you need to understand what it was trying to be. The operating system shipped exclusively on low-cost education laptops from nine manufacturers: Acer, Asus, Dell, Dynabook, Fujitsu, HP, JK-IP, Lenovo, and Positivo. Microsoft’s own contribution was the Surface Laptop SE, a $249 machine with an all-plastic body, an 11.6-inch 1366x768 display, 4GB of RAM, and an Intel Celeron processor. It was, by design, the kind of hardware that schools buy in bulk and students abuse relentlessly.

The software was Windows 11 stripped down to fit the education use case. Microsoft removed the Windows Store entirely, restricting app installation to IT administrators deploying through Microsoft Intune. Snap Layouts offered only two options instead of six. The Widgets feature was removed to minimize distraction. File Explorer opened full-screen by default. Edge came with Chrome extension support enabled by default, a tacit acknowledgment that schools live in the Google ecosystem. The idea was sound on paper: give IT administrators a locked-down, manageable Windows environment that could compete with ChromeOS on price and simplicity.

The problem was that Windows 11 SE was fundamentally Windows 11 underneath. And Windows 11, no matter how you strip it down, was never designed to run well on a $249 Celeron laptop with 4GB of RAM. ChromeOS was designed from the ground up for exactly that hardware profile. That distinction proved decisive.

A Pattern of Failed Attempts

Windows 11 SE was not Microsoft’s first try at cracking the education market with a stripped-down operating system. In 2017, the company introduced Windows 10 S, a standalone edition that restricted users to Microsoft Store apps in the name of security and performance. Rebranded as S Mode in 2018, it generated immediate pushback from users who found it too limiting, and most who tried it switched back to full Windows within days. The approach failed because it asked users to accept restrictions without offering enough benefit in return.

Windows 11 SE learned some lessons from S Mode. It targeted a narrower audience (K-8 schools rather than consumers), gave IT administrators more control, and bundled Microsoft Office rather than relying on the anemic selection in the Microsoft Store. But it repeated the fundamental mistake: trying to compete with a purpose-built lightweight operating system by restricting a heavyweight one. ChromeOS is lean because it was built that way. Windows 11 SE was lean because Microsoft removed features from an operating system that expects more resources than education hardware provides.

Why ChromeOS Won the Classroom

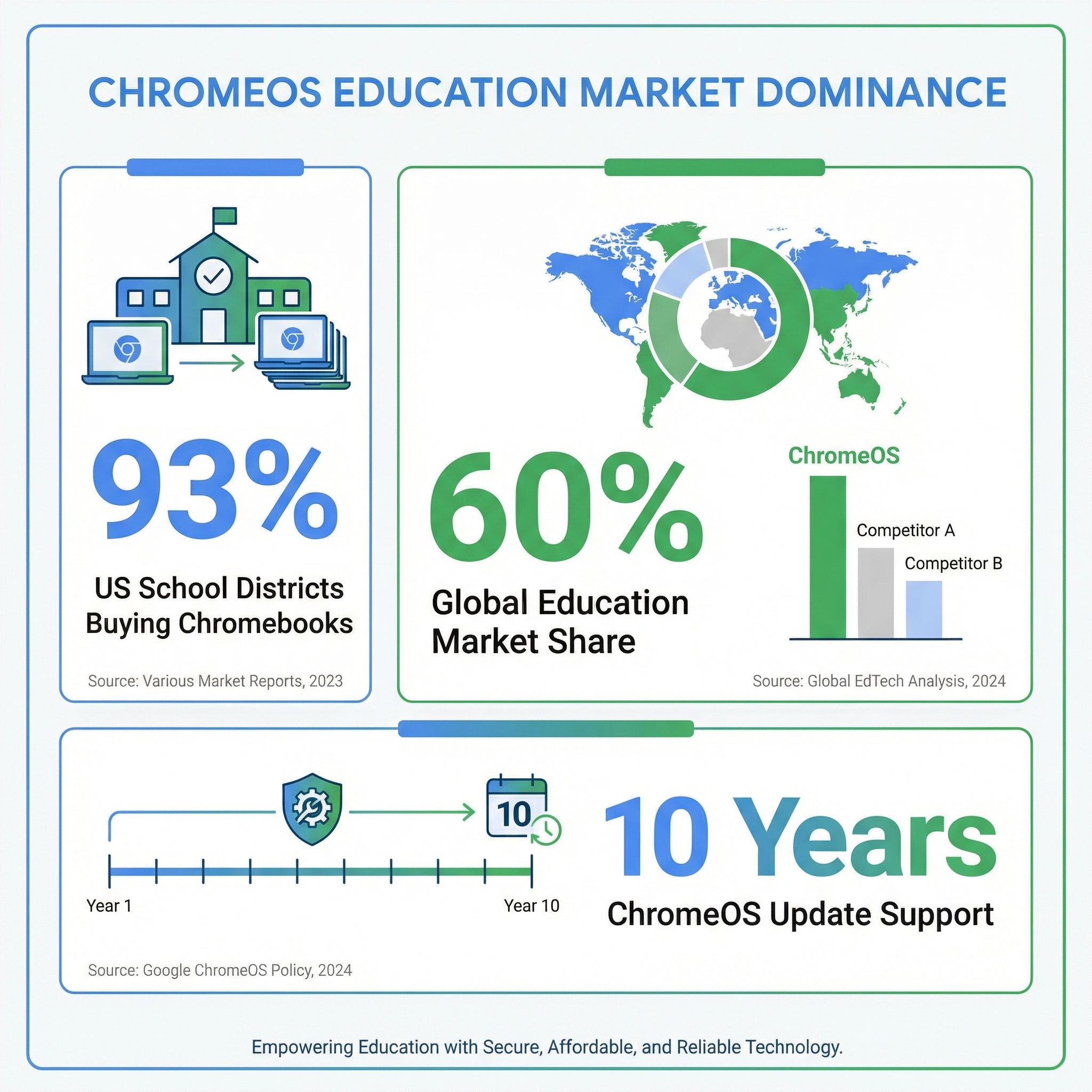

The numbers paint a clear picture of how thoroughly ChromeOS dominates education. According to About Chromebooks, citing EdWeek Market Brief data, 93 percent of US school districts reported purchasing Chromebooks in 2025, a nine-percentage-point increase from 2023. That statistic measures purchasing intent rather than exclusive deployment, and many districts also buy Windows laptops and iPads, but the trend is unmistakable. ChromeOS holds roughly 60 percent of the global education device market, and in the United States the installed base is substantially larger than that.

ChromeOS won for reasons that have little to do with marketing and everything to do with what schools actually need. The first is price. A complete Chromebook setup for a student costs $250 to $350 including the keyboard, while a comparable Windows 11 SE device was priced similarly but delivered a worse experience on equivalent hardware. Our Chromebook vs. iPad comparison found that iPad setups run $530 to $730 with necessary accessories, making Chromebooks the clear value winner for budget-conscious districts.

The second advantage is management. Chrome OS was designed for fleet deployment from day one. Through the Google Admin Console, IT administrators can manage thousands of devices remotely, push policies, restrict access, and monitor usage without touching individual machines. Windows 11 SE offered similar capabilities through Microsoft Intune, but the management model was grafted onto an operating system that was not built for it. Schools that had already invested in Google Workspace for Education found that Chromebooks integrated seamlessly with the tools their teachers and students already used.

The third is the update cycle. Google extended automatic update support for ChromeOS devices to ten years in 2023, up from eight. Windows 11 SE, by contrast, is losing all support after just five years. That difference matters enormously for schools operating on tight budgets and multi-year procurement cycles. A Chromebook purchased in 2024 will receive security updates through 2034. A Windows 11 SE device purchased at the same time becomes a security liability in October 2026.

But ChromeOS Has Problems Too

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging that ChromeOS is not without its own challenges, and that the education device market is more complicated than “Chromebooks good, everything else bad.” Chromebook shipments have been declining since the pandemic-fueled boom of 2020-2021, falling from a peak of roughly 37 million units to stabilize around 22 million annually. The post-pandemic demand cliff was real, and the expiration of Emergency Connectivity Fund dollars that powered pandemic-era purchases has tightened school budgets.

The durability of education Chromebooks remains a genuine concern. Gartner analysts have noted Chromebooks were “losing market share due to their limited customer base and inferior build quality”, and environmental advocates like US PIRG have raised questions about the e-waste implications of millions of low-cost devices with limited lifespans. The ten-year update commitment helps, but hardware failure rates in school environments remain stubbornly high regardless of the operating system running on the device.

There is also the question of whether ChromeOS dominance in education creates its own problems. Our coverage of the screen time debate in education explored how school-issued devices, including Chromebooks, have become a source of distraction rather than learning when deployed without adequate management policies. Teachers report that students use school-issued Chromebooks to watch YouTube, play games, and browse social media during class. The device management tools exist to prevent this, but many schools barely scratch the surface of what is available.

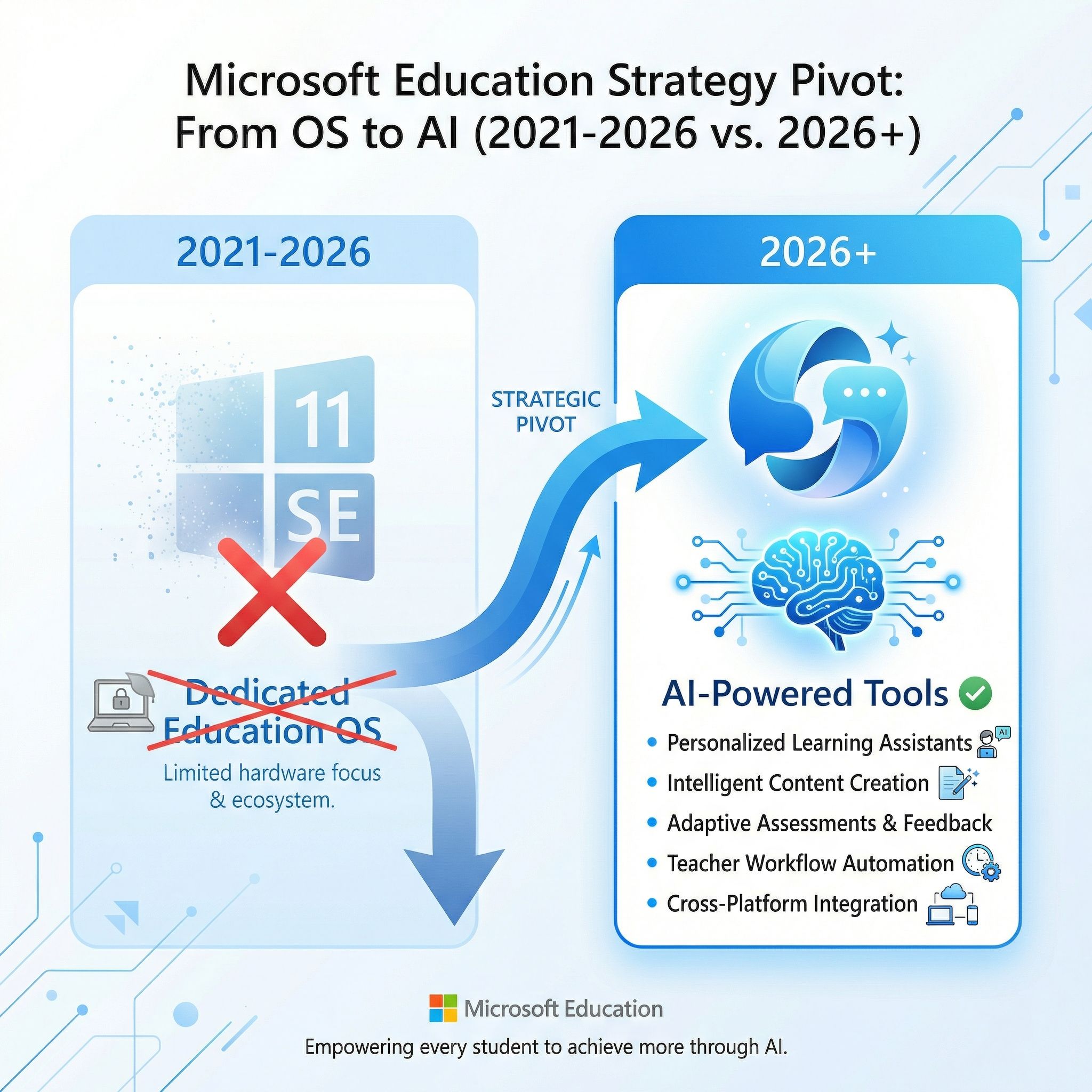

Microsoft’s Pivot: AI Over Operating Systems

The death of Windows 11 SE does not mean Microsoft is abandoning education. It means the company is pursuing a fundamentally different strategy. At BETT 2026 in London, Microsoft announced 18 major education updates centered on AI rather than operating systems, rolling out a Copilot Teach module for lesson planning and resource creation, a Study and Learn agent for students aged 13 and older, and a new Learning Zone app that transforms ideas into interactive lessons using AI on Copilot+ PCs.

The shift in strategy is telling. Rather than trying to compete with ChromeOS on price and simplicity at the operating system level, Microsoft is betting that AI-powered teaching tools integrated into Microsoft 365 will make the underlying operating system irrelevant. The Teach module helps educators generate standards-aligned lesson plans from over 35 countries, create rubrics, build quizzes, and adapt materials by reading level. The Study and Learn agent supports revision and practice through adaptive exercises. All of these tools run on standard Windows 11 and require no additional Copilot license for Microsoft 365 Education customers.

This is a smarter competitive approach than Windows 11 SE ever was. Instead of asking schools to adopt an inferior operating system because it is cheap, Microsoft is offering tools that add value on top of whatever platform schools already use. Whether it will be enough to reverse ChromeOS momentum in education is another question entirely, but it at least addresses the market with Microsoft’s actual strengths, software services and AI, rather than trying to win on hardware economics where Google has an insurmountable advantage.

What Happens to Schools Running Windows 11 SE

For the relatively small number of schools that adopted Windows 11 SE devices, the October 2026 deadline creates a real, if manageable, problem. After that date, devices will continue to function but will receive no security updates, no technical support, and no feature updates. Microsoft recommends transitioning to a device that supports another edition of Windows 11, but many Windows 11 SE devices were specifically engineered for that operating system and may not have the hardware resources to run full Windows 11 adequately.

The most practical path for affected schools depends on their existing ecosystem. Schools already invested in Google Workspace for Education have a natural migration path to Chromebooks, and the transition is straightforward since the web applications and student accounts carry over seamlessly. Schools deeply invested in Microsoft 365 may choose to upgrade to standard Windows 11 devices, particularly if they want access to the new AI-powered Copilot education tools. Either way, the Windows 11 SE hardware itself is likely headed for recycling.

For schools evaluating Chromebooks, the landscape of education-focused models has improved significantly since Windows 11 SE launched. Ruggedized designs with MIL-STD durability testing, spill-resistant keyboards, and customer-replaceable components are now standard across the education Chromebook lineup from manufacturers like Lenovo, Acer, and HP. Paired with Google’s ten-year update commitment, these devices offer a total cost of ownership that no Windows education device has been able to match.

The Lesson That Keeps Getting Learned

The pattern at this point is hard to miss. Microsoft has spent a decade trying to build a lightweight operating system for education and has failed every time. Windows 10 S restricted users without delivering enough value. Windows 11 SE targeted the right market but used the wrong foundation. Each attempt started with the premise that Windows could be made to compete with ChromeOS through subtraction, by removing features until what remained was simple and fast enough for a $250 laptop. Each time, the result was an operating system that felt like a compromised version of something better rather than a purpose-built solution for its intended audience.

ChromeOS works in schools because it was designed for the constraints of education computing. It boots fast because it was built to boot fast, not because someone removed startup services from a heavier operating system. It runs well on cheap hardware because its resource requirements are genuinely low, not because someone disabled features to free up memory. It is manageable at scale because fleet management was a design goal from the beginning, not an afterthought bolted onto a consumer operating system.

Microsoft seems to have finally internalized this lesson with its AI-first education strategy. Instead of trying to out-ChromeOS ChromeOS, the company is competing on different ground entirely, offering AI-powered tools that work across platforms and add value that ChromeOS does not natively provide. Whether that approach succeeds will depend on execution, adoption, and whether schools are willing to pay for AI-powered teaching tools or view them as nice-to-have extras rather than essentials.

For now, though, the classroom belongs to ChromeOS. Not because Chromebooks are perfect, not because ChromeOS lacks problems of its own, but because Google built the right tool for the job while Microsoft kept trying to reshape the wrong one.