What Can Your School Actually See on Your Kid's Chromebook?

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

When your child comes home with a school-issued Chromebook, you’re probably thinking about homework assignments and educational apps. What you might not realize is that the device likely contains sophisticated monitoring software that can track far more than just what websites your kid visits during class. Tools like GoGuardian, Linewize, and Securly have quietly become standard in American schools, and their capabilities extend well beyond keeping students off YouTube during algebra.

This isn’t a simple story of schools overreaching or technology gone wrong. It’s a genuine tension between protecting students from real threats and respecting their privacy and development. After digging through research from the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Center for Democracy and Technology, I’ve come to appreciate how complicated this debate really is. Parents already face tough decisions about which devices to choose for school, but the monitoring question adds a whole new dimension. The technology does help schools intervene in genuine crises. But it also creates a surveillance infrastructure that disproportionately affects certain students and raises serious questions about what we’re teaching kids about privacy in the digital age.

What the Monitoring Software Actually Does

The surveillance capabilities of school Chromebook monitoring software go far beyond what most parents imagine. According to the EFF’s investigation, GoGuardian alone monitors approximately 27 million students across 10,000 schools. That’s roughly one in five K-12 students in America with their digital activity under constant observation.

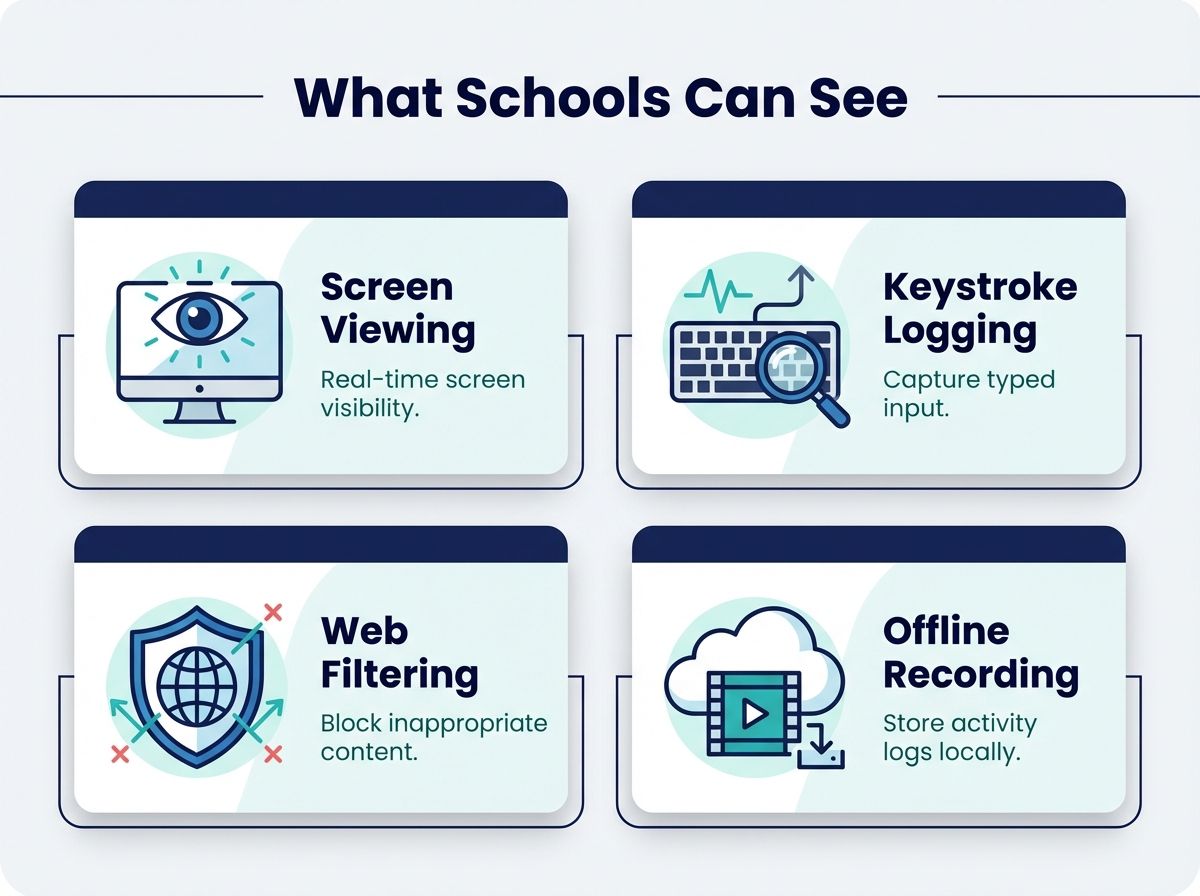

At the most basic level, these tools provide web content filtering, blocking categories of sites like adult content, gambling, or social media during school hours. But modern monitoring goes much deeper. Teachers can view students’ screens in real time, seeing exactly what’s on every device in the classroom simultaneously. Some software takes periodic screenshots, creating a visual record of student activity. Keystroke logging captures what students type, including in private documents. And perhaps most concerning to privacy advocates, some tools like Linewize continue monitoring when students are offline, recording activity locally and then uploading it to school servers when the device reconnects to the internet.

The offline monitoring capability means that a private journal your child writes on the device during a family road trip could be uploaded and analyzed the moment they return to a wifi network. One parent discovered this capability accidentally when a teacher activated a camera during virtual school to check if a student was nearby. How long the teacher had been watching before being noticed remained unknown.

Search history, email content, documents, browsing patterns, and even timestamps of when the device is opened and closed all flow into school administrative dashboards. The data creates what the EFF calls “comprehensive student profiles” that persist throughout a student’s educational career. And under federal law, schools can collect this data without explicit parental consent for students over 13 if they deem it necessary for legitimate educational purposes.

The Safety Argument: Why Schools Deploy This Technology

School administrators and monitoring software vendors point to real, serious threats that this technology helps address. The most compelling argument involves student safety: detecting signs of self-harm, suicide ideation, or potential violence before tragedy strikes.

GoGuardian’s Beacon product specifically scans student activity for concerning keywords and patterns related to mental health crises. The company emphasizes suicide prevention as a core use case, and there are documented cases where monitoring alerts led to life-saving interventions. When a student Googles “how to end it all” or types concerning content into a document, the system flags it for immediate review by trained staff. No parent would argue against a school notifying them if their child searched for methods of self-harm.

Beyond mental health, schools point to the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), which requires schools receiving federal funding to implement internet safety measures. While CIPA specifically states it does not require tracking individual students, many districts interpret the law as justification for comprehensive monitoring. School IT administrators I spoke with described genuine dilemmas: they’ve caught students accessing dangerous content, planning fights, or being targeted by online predators through monitoring systems.

The pandemic accelerated adoption dramatically. When students took devices home for remote learning, schools felt increased responsibility for what happened on those machines. One district administrator told EdSurge they needed “granular control” to ensure student safety during the chaos of 2020 and 2021. What began as an emergency measure became permanent infrastructure.

The Privacy Argument: Chilling Effects and False Positives

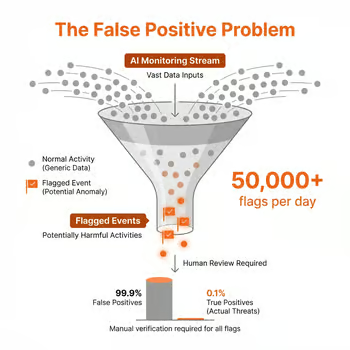

The EFF’s deep investigation into GoGuardian paints a concerning picture of a system that flags far more content than it accurately identifies as harmful. By design, the software is what researchers call a “red flag machine.” The EFF found that false positives heavily outweigh accurate detections, with some large school districts receiving over 50,000 flags per day. The sheer volume means administrators often can’t meaningfully review each alert, and benign student behavior gets caught in the net.

Consider a student researching the opioid crisis for a health class assignment, or looking up information about eating disorders to help a friend. Both trigger keyword alerts. A student curious about their own identity might search for LGBTQ+ resources, information about gender identity, or mental health support for questioning youth. Those searches flag too. For students in unsupportive home environments, the knowledge that school officials can see these searches might prevent them from seeking help at all.

The Center for Democracy and Technology research found this “chilling effect” is real. Students who know they’re monitored are less likely to search for sensitive health information, explore questions about identity, or express authentic thoughts in school assignments. One parent quoted in CDT’s report worried about “the long-term ramifications for children who are taught to hand over data to Google without question,” noting that her daughter was being “forced into that at such an early age, when she doesn’t know any better.”

The privacy advocates’ strongest argument is about developmental harm. Adolescence involves identity exploration, questioning authority, making mistakes, and learning from them. A generation of students growing up under constant surveillance may learn that privacy doesn’t exist, that authority figures always watch, and that any curiosity or deviation from the norm gets flagged and recorded. These lessons might shape how they view civic liberties and institutional trust for the rest of their lives.

The Equity Problem: Who Gets Surveilled?

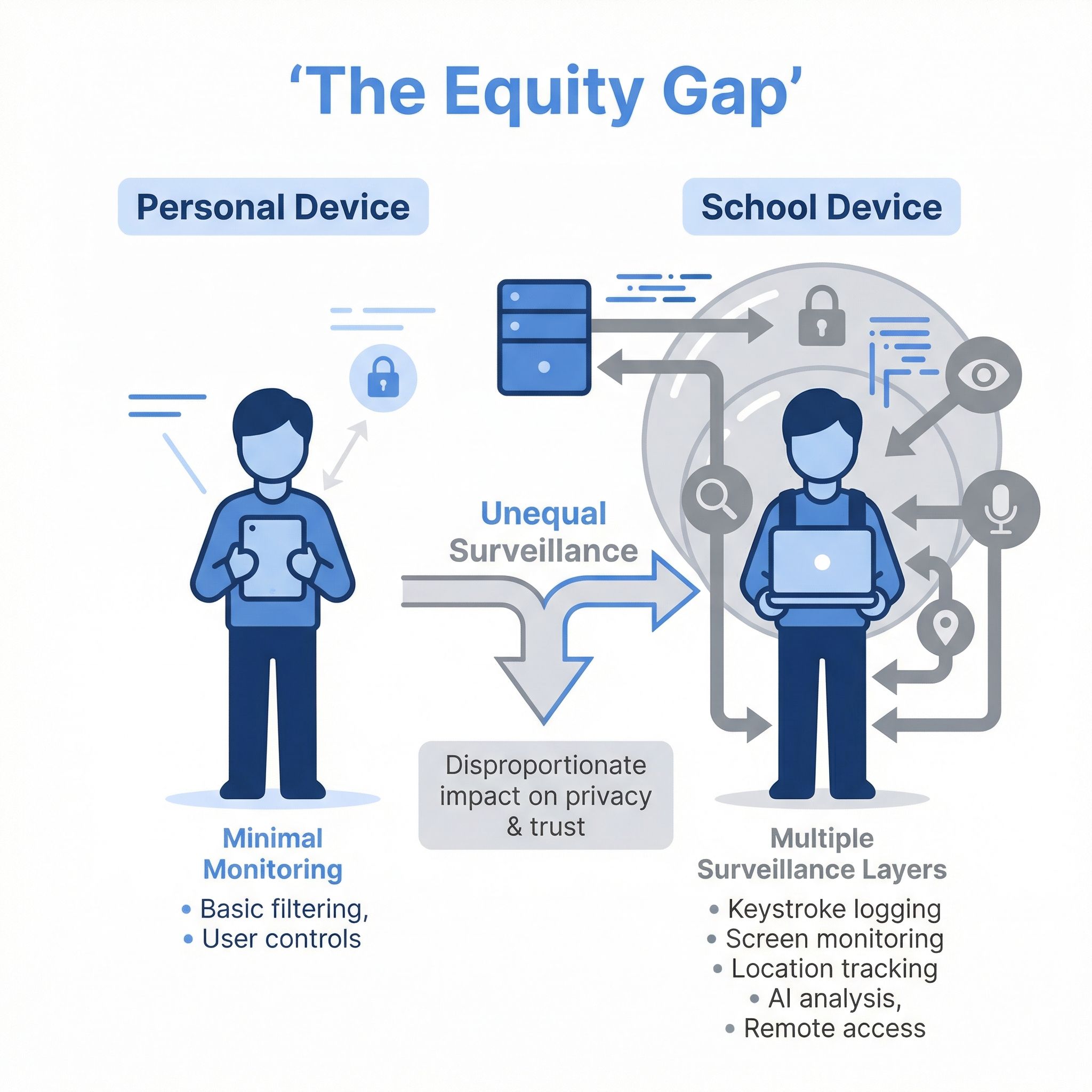

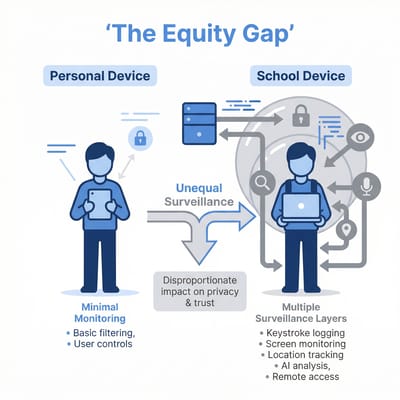

Here’s where the surveillance debate gets particularly uncomfortable. According to CDT research, 81 percent of teachers report their schools use student activity monitoring software. But only one in four say that monitoring is limited to school hours. That means the majority of schools are tracking students at home, during evenings, and on weekends.

The problem is who has alternatives. Students from families who can afford personal laptops, tablets, and phones can do their personal browsing on unmonitored devices. Students from lower-income families who rely entirely on school-issued equipment have no such option. They face what researchers call “two layers of monitoring,” with device-level surveillance stacked on top of cloud document scanning that affects all students.

Cody Venzke, senior policy counsel at CDT, described the disparity: students who depend on school-issued devices may face monitoring of their screens, open applications, and browsing history 24/7, including surveillance that students using personal devices never encounter. The digital divide that school Chromebook programs were designed to address now comes with an unintended cost: the students who most needed access to technology are also the ones subject to the most comprehensive surveillance.

DeVan Hankerson Madrigal, CDT’s Research Manager, put it bluntly: “It’s been long demonstrated that historically marginalized groups of students have fewer educational opportunities than their peers. Those disparities can be compounded through the technologies that schools are using, not only in a lack of access, but also in saddling those students with surveillance technology when that access is provided.” In other words, the very programs designed to close the digital divide may be widening a privacy divide that tracks along the same socioeconomic lines.

A Better Approach: School Hours Only

Not every district has embraced round-the-clock monitoring, and some have found that responsible limits work just fine. Boulder Valley School District in Colorado, with 30,000 students across 55 schools, uses GoGuardian but limits its classroom monitoring features to school hours only. Their approach offers a practical model for districts that want to balance safety with student privacy.

Andrew Moore, the district’s CIO, explained the philosophy to researchers: “We feel that’s more of a parent’s or guardian’s responsibility, and that it also straddles that fine line between what students are doing in their off hours. Whether someone watching a movie on Netflix is a good thing or a bad thing depends on your perspective, but it’s really not in the school district’s purview to say thumbs up or thumbs down to what you’re doing in the off hours.”

The district still filters web content at all times on school devices, blocking categories like adult content and gambling. But the active surveillance features, where teachers can see student screens and the system logs detailed activity, are disabled when students leave campus. It’s a middle-ground approach that acknowledges both the legitimate need for classroom management and the boundaries of school authority.

Moore encouraged other districts not to give up when implementing privacy-respecting policies: “It’s easy to get frustrated when you don’t get it right every single time.” He advises exploring different tools and configurations rather than defaulting to maximum surveillance. Schools can protect students without extending their authority into every moment of a child’s digital life.

What Parents Should Ask Their School District

If your child uses a school-issued Chromebook, you have both the right and responsibility to understand what the school can see. Here are the specific questions to ask your district’s IT department or school board:

What monitoring software is installed on student devices? Get the specific product names (GoGuardian, Linewize, Securly, Lightspeed, etc.). Each has different capabilities and default settings.

Is monitoring limited to school hours, or does it continue at home? This is the most important question. The difference between school-hours-only and 24/7 monitoring is enormous.

What specific activities trigger alerts? Understanding the keyword and content categories that flag student activity helps you have realistic conversations with your child about what’s being watched.

How long is monitoring data retained, and who can access it? Some schools keep records throughout a student’s entire enrollment, while others purge data regularly. Ask whether just IT staff see the dashboards or if principals and individual teachers also have access. The retention period and breadth of access together determine how much of a profile the school builds on your child and how many people can view it.

What happens when something is flagged, and is there an opt-out? Understanding the review process helps you assess whether false positives are likely to cause problems for your student. A school that has trained counselors reviewing alerts is very different from one where a teacher gets a raw notification. Also ask whether your district allows students to use personal devices instead, though this often means losing access to school-provided software and services.

The Bigger Picture: What Are We Teaching?

School Chromebook surveillance isn’t a simple case of overreach or necessity. Both things are true: schools have legitimate reasons to protect students, and the current implementation often goes far beyond what’s needed or appropriate. The technology that can save lives through suicide prevention can also catalog a teenager’s private questions and curiosities throughout their formative years.

For parents, the practical path forward involves both engagement and alternatives. Ask your school board the hard questions about monitoring policies. Advocate for school-hours-only approaches like Boulder Valley’s model. And if your child needs a device for personal use, consider that an inexpensive personal Chromebook might be worth the investment in their privacy.

The surveillance debate ultimately reflects a broader question about how we raise digital citizens. Do we teach children that authority figures should have access to their every digital move? Or do we demonstrate that privacy is a value worth protecting, even when it’s inconvenient? The answer we choose in our schools shapes the adults these students will become.

Affordable Personal Chromebooks

If you’re looking for a Chromebook your child can actually own for personal use at home, without school monitoring software, here are some budget-friendly options worth considering. For a deeper look at what makes a good device for younger users, see our full guide to the best Chromebooks for kids.

Lenovo IdeaPad 3i Chromebook

- ✓Under $170

- ✓8GB RAM

- ✓large 15.6-inch display

- ✓10-hour battery

- ✗No touchscreen

- ✗heavier at 3.5 lbs

- ✗basic plastic build

Lenovo Chromebook Duet

- ✓Tablet flexibility

- ✓included keyboard

- ✓very portable

- ✓good display

- ✗Small 10.1-inch screen

- ✗limited multitasking RAM

- ✗cramped keyboard

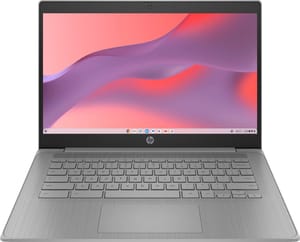

HP Chromebook 14a (2023)

- ✓Excellent 14-hour battery

- ✓decent display

- ✓slim design

- ✗Only 4GB RAM on base model

- ✗limited storage

- ✗not the fastest processor

The key difference with any of these personal devices: you control them. No school monitoring software, no flagged searches, no administrators viewing your child’s screen. For sensitive personal browsing, identity exploration, or just watching Netflix without a teacher closing tabs, that privacy is worth the modest investment.