RISC-V Mini PCs in 2026: What Actually Works, What Doesn't, and Who Should Care

Published on by Jim Mendenhall

Listen to this article:

For years, RISC-V has been the open-source chip architecture that was always “almost ready.” Conference talks touted its potential, academic papers praised its elegance, and the occasional development board trickled out for hardware enthusiasts willing to tolerate bare PCBs and kernel panics. But something tangible has shifted over the past twelve months. Companies like Milk-V and DeepComputing are now shipping real, purchasable products with standard Mini-ITX form factors, PCIe slots, NVMe storage, and the ability to boot Ubuntu from an ISO file. The question is no longer whether RISC-V desktop hardware exists. The question is whether any of it is worth buying.

The honest answer, as of February 2026, is a nuanced one that depends entirely on what you want to do. If you’re expecting to replace your Beelink SER8 or any mainstream x86 mini PC, you’ll be disappointed. Current RISC-V boards deliver performance roughly on par with an Intel Core 2 Duo from 2008, and the software ecosystem has enough gaps to frustrate anyone expecting a plug-and-play experience. But if you’re a developer building for RISC-V, a tinkerer who enjoys the bleeding edge, or someone who simply believes in open-source silicon and wants to put money behind that belief, there has never been a better time to jump in. The hardware is genuinely impressive for where the architecture stands, and the trajectory is steep enough to make today’s boards look like the foundation of something much bigger.

The Hardware Landscape

The RISC-V mini PC market has stratified into clear tiers over the past year, and the range of options is surprisingly broad for an architecture most people still consider experimental.

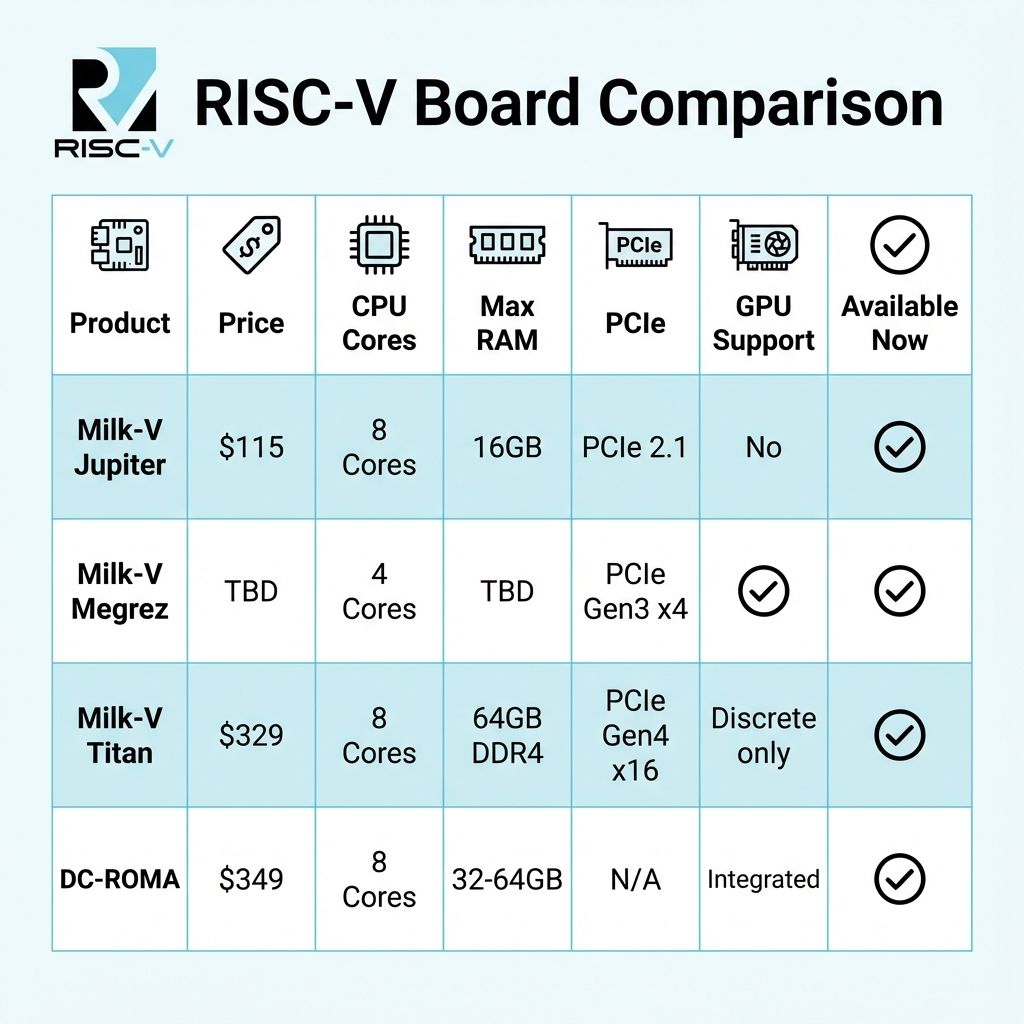

At the entry level, the Milk-V Jupiter remains the most accessible way to build a RISC-V PC. Starting at $60 for a 4GB model with the Spacemit K1 SoC, it’s a full Mini-ITX motherboard with front panel I/O, dual Gigabit Ethernet, WiFi 6, an M.2 NVMe slot, and an open-ended PCIe 2.1 slot. Jeff Geerling’s extensive testing found it performed at roughly Raspberry Pi 3 levels for CPU-bound tasks, but the real story was how well everything just worked. Front panel audio, USB 3.0, ATX power, NVMe storage — it all functioned out of the box. The $115 top-end model with the Spacemit M1 and 16GB RAM is the one most people should consider, and it represents the world’s first Mini-ITX board supporting both the RVA22 profile and RVV 1.0 vector extensions.

The Milk-V Megrez steps up to an ESWIN EIC7700X processor with quad-core SiFive P550 cores clocked at up to 1.8 GHz. The P550 is a meaningfully more capable core than the Spacemit’s X60, featuring a 13-stage out-of-order pipeline with triple-issue execution. What makes the Megrez particularly interesting is its 19.95 TOPS NPU and a PCIe Gen3 x4 slot that Milk-V claims has been tested with an AMD Radeon RX 7900 XTX. That GPU claim, if reproducible in practice, would make the Megrez the first RISC-V board capable of serious graphics work, though independent verification remains scarce.

Then there’s the Milk-V Titan, which arrived in mid-2025 and represents the current high-water mark for RISC-V desktop hardware. Powered by the UltraRISC UR-DP1000, it packs eight UR-CP100 cores running at up to 2.0 GHz — the most capable RISC-V cores in mass production today. The Titan supports standard DDR4 DIMMs up to 64GB with ECC, PCIe Gen4 x16 for discrete graphics cards, NVMe via PCIe Gen4 x4, and crucially, UEFI boot with ACPI support. That last detail matters enormously: it means you can install mainstream Linux distributions from standard ISO images, just like on an x86 machine. At $329 on Arace, it’s not cheap for what amounts to Raspberry Pi 4-class single-core performance, but the I/O capabilities and expandability are in a different league entirely.

One critical caveat about the Titan: it has no integrated graphics. You’ll need to install a discrete GPU via the PCIe x16 slot for any display output, which adds $50-150 to the total build cost and limits which graphics cards have working drivers under Linux on RISC-V.

Outside of Milk-V, DeepComputing’s DC-ROMA AI PC takes a different approach. Built around the ESWIN EIC7702X with eight SiFive P550 cores and a 50 TOPS NPU, the DC-ROMA ships as a complete mainboard compatible with Framework laptop chassis, or in a Cooler Master desktop case. Starting at $349 with 32GB RAM, it comes with Ubuntu 24.04 LTS pre-installed and represents perhaps the most turnkey RISC-V desktop experience available today. Canonical’s partnership with DeepComputing signals that at least one major Linux distributor is taking RISC-V seriously enough to provide first-party support.

What Actually Works (and What Doesn’t)

Here’s the practical reality of using a RISC-V board as a computer in 2026, based on community testing and real-world reports.

Docker and containers work well. This is probably the best use case for RISC-V boards right now. The Docker ecosystem has improved dramatically for RISC-V, with multi-architecture images becoming common thanks to the groundwork ARM laid in making build toolchains architecture-agnostic. Running Pi-hole, AdGuard Home, Gitea, or other lightweight self-hosted services is entirely practical. If you’ve read our guide to the self-hosting renaissance, the RISC-V boards can handle many of the same workloads, just at lower throughput.

Basic desktop computing works, with caveats. LibreOffice, Chromium, and simple GUI applications run under distributions like Bianbu Linux, Ubuntu, and Fedora. But “runs” and “runs well” are different things. Jeff Geerling reported that YouTube video playback was only smooth at 240p on the Jupiter, and that’s a limitation you’ll feel across the board. Hardware video decoding support varies by SoC, and software decoding at 1080p is beyond what current RISC-V cores can handle smoothly.

NVMe storage and basic PCIe devices work. You’ll get PCIe Gen2 speeds on the Jupiter and Gen4 on the Titan, and NVMe SSDs are recognized and perform as expected. Network cards and simple PCIe adapters generally work. Full discrete GPU support is more complicated — driver availability depends on the specific GPU, SoC, and kernel version, and you should expect to spend time in forums getting things configured.

Media server duties are a stretch. Plex or Jellyfin will run, but transcoding is essentially off the table. Direct play of media files works, but if you need your server to transcode for remote clients, an Intel N100 mini PC at a similar price point will dramatically outperform any current RISC-V board.

Compilation and development targeting RISC-V work well. This is arguably the intended use case, and the boards handle it capably. Building RISC-V binaries natively rather than cross-compiling is valuable for developers, and the Jupiter and Titan both complete Linux kernel compilation tests successfully.

The Power Efficiency Question

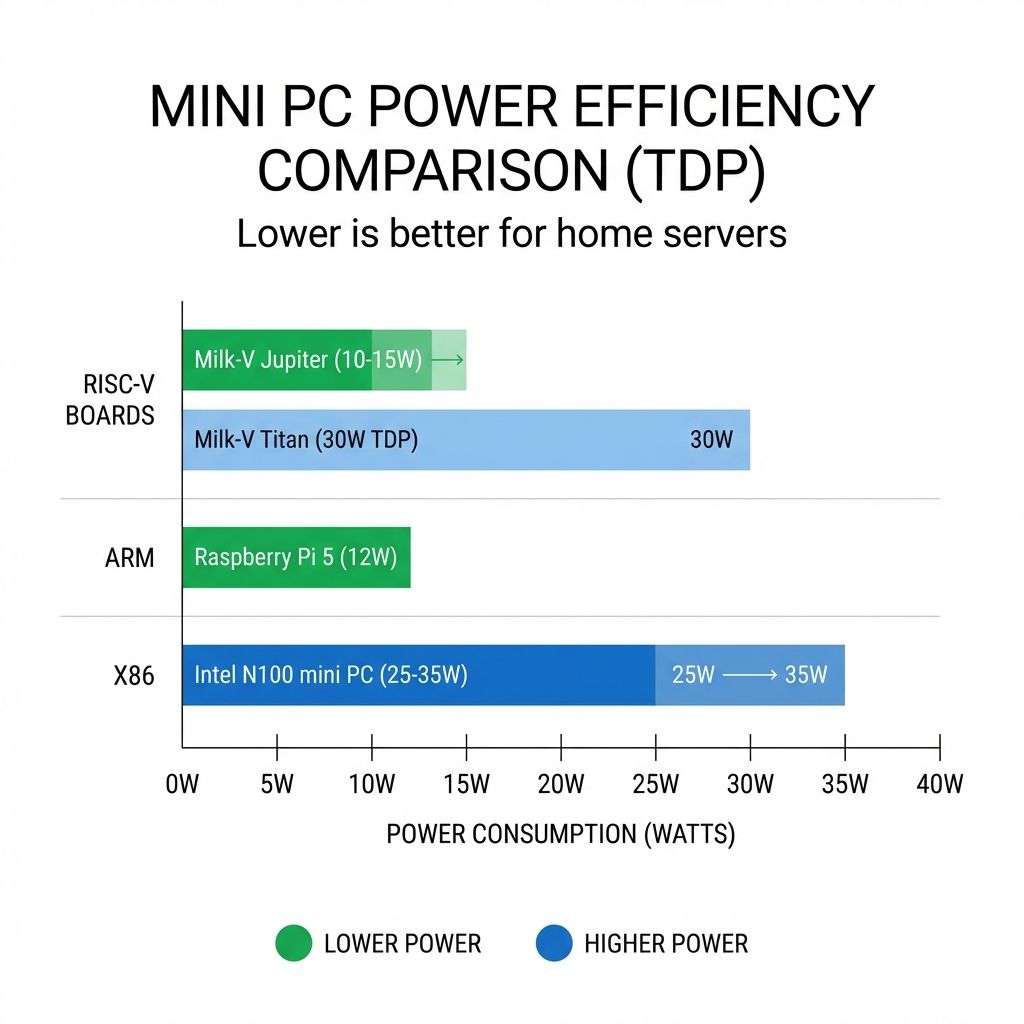

One area where RISC-V boards might eventually compete with x86 mini PCs is power consumption, but the story is more complex than you’d expect. The Milk-V Jupiter draws around 10-15 watts under load, comparable to a Raspberry Pi 5 and well below the 25-35W typical of Intel N100 mini PCs running Docker workloads. The Titan’s UR-DP1000 has a 30W TDP, putting it in N100 territory for power draw but delivering significantly less computing power per watt.

The efficiency math doesn’t favor RISC-V today if you’re optimizing for performance per watt. An Intel N150 system can run the same containerized services at higher throughput while sipping similar power. But RISC-V’s efficiency is improving with each generation of cores, and the architecture’s simplicity gives chip designers room to optimize without the legacy overhead that x86 carries. If you’re running lightweight services where the CPU is mostly idle — DNS filtering, a VPN endpoint, a small Git server — the Jupiter’s low idle power draw becomes genuinely attractive.

The Software Story: Better Than You Think, Worse Than You’d Like

The RISC-V software ecosystem has reached a tipping point where it’s genuinely usable but still requires patience. Multiple Linux distributions now provide official or well-maintained RISC-V builds. Fedora’s V-Force initiative offers images for numerous boards, and the Titan’s UEFI support means you can boot Fedora, Ubuntu, or Debian from standard ISO images without board-specific builds.

The RVA22 and RVA23 profiles have been critical in reducing fragmentation. These standardized specifications define a baseline set of extensions that software can target, meaning a binary compiled for RVA22 should run on any RVA22-compliant board. This is analogous to what ARM achieved with its architecture profiles, and it eliminates the early RISC-V problem of every board needing its own kernel and userspace builds. The upcoming RVA23 profile brings mandatory support for additional vector extensions and data types that matter for AI workloads, and it’s the profile that Ubuntu 26.04 LTS will target for high-performance builds.

Package availability in distribution repositories is steadily improving but still has gaps. Most common server and development tools are available. Desktop applications are more hit-or-miss, particularly anything that relies on proprietary codecs, hardware-accelerated graphics, or architecture-specific optimizations. Electron apps are largely absent, which cuts off a significant chunk of modern desktop software.

Who Should Actually Buy One

Let’s be direct about this. If you want a mini PC for local LLM inference, a home theater PC, or a general-purpose desktop replacement, buy an x86 or ARM system. The performance gap is too wide and the software ecosystem too immature for RISC-V to compete in those roles today.

But there are several groups for whom a RISC-V board makes genuine sense right now. Software developers who need to test and optimize code for RISC-V should consider the Titan as a native development platform; cross-compilation works but nothing replaces testing on real hardware. Educators and students studying computer architecture will find RISC-V boards invaluable for understanding a modern ISA that isn’t buried under decades of backward-compatible cruft. Self-hosting enthusiasts who already run multiple servers and want to experiment with a third architecture alongside x86 and ARM can deploy lightweight services on a Jupiter without breaking the bank. And open-source advocates who want to vote with their wallets for a fully open instruction set architecture will find the current crop of boards a tangible way to support the ecosystem.

The strongest recommendation in the current lineup depends on your budget and goals. The Milk-V Jupiter at $115 (16GB M1 model) is the best starting point for experimentation: it’s cheap enough to justify as a learning tool, the Mini-ITX form factor makes it feel like a real PC, and the community around it is active and helpful. The Titan at $329 is the serious option for developers who need PCIe Gen4 bandwidth, DDR4 DIMM flexibility, UEFI boot, and the closest thing to a standard PC experience that RISC-V currently offers. The DeepComputing DC-ROMA at $349 is the most turnkey option, arriving pre-assembled with Ubuntu and 32GB RAM. Just keep in mind that Titan requires adding a discrete GPU, so budget an extra $50-150 for a compatible card.

Where This Is Heading

The trajectory of RISC-V desktop hardware is genuinely exciting, even if the present is humbling. The Milk-V Jupiter 2, expected in April 2026, will bring RVA23 compliance, a significant CPU performance bump, 60 TOPS of AI acceleration, and 10GbE networking to a $199 board. That’s a generational leap from the original Jupiter’s capabilities. Tenstorrent’s Ascalon cores have demonstrated benchmark results approaching AMD Zen 5 parity in IP licensing tests, and NVIDIA’s announcement that it’s porting CUDA to RISC-V signals that the GPU computing ecosystem is taking the architecture seriously.

None of that helps you today, and it’s important not to buy hardware based on roadmap promises. But the direction is clear: RISC-V is following a compressed version of the path ARM took from embedded curiosity to mainstream computing platform. ARM took roughly a decade to go from the first Raspberry Pi to Apple’s M1 dominating laptop benchmarks. RISC-V won’t take that long because it benefits from ARM having already proven that a non-x86 architecture can compete, and from an open ecosystem that lets any company design competitive cores without licensing fees.

For now, a RISC-V mini PC is a statement purchase as much as a practical one. You’re buying into a future that isn’t fully here yet, and you should go in with eyes open about the limitations. But the hardware is real, the prices are reasonable, and for the right use cases, these boards are genuinely usable machines. That alone marks a turning point worth paying attention to.